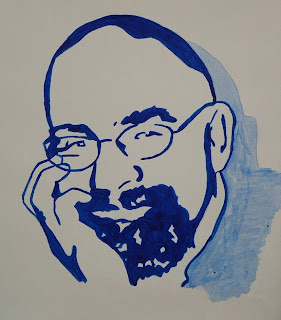

Douglas Cowan is a leading scholar working in the area of new religions. Formerly he taught at the University of Missouri – Kansas City, and he now teaches at Renison College/University of Waterloo. He is the author of a number of books, including Cults and New Religions: A Brief History (Blackwell, 2007); Cyberhenge: Modern Pagans on the Internet (Routledge, 2005); The Remnant Spirit: Conservative Reform in Mainline Protestantism (Praeger, 2003); and Bearing False Witness?: An Introduction to the Christian Countercult (Praeger, 2003). (Painting by Paul Thomas, Ph.D.)

Douglas Cowan is a leading scholar working in the area of new religions. Formerly he taught at the University of Missouri – Kansas City, and he now teaches at Renison College/University of Waterloo. He is the author of a number of books, including Cults and New Religions: A Brief History (Blackwell, 2007); Cyberhenge: Modern Pagans on the Internet (Routledge, 2005); The Remnant Spirit: Conservative Reform in Mainline Protestantism (Praeger, 2003); and Bearing False Witness?: An Introduction to the Christian Countercult (Praeger, 2003). (Painting by Paul Thomas, Ph.D.)

Doug also has teaching and writing experience and a great interest in religion and popular culture. He has articles coming out on the religious underpinning of the 1953 version of War of the Worlds, and on the apocalyse and millennium in American popular culture. He regularly teaches courses at the University of Waterloo on Religion and Popular Film, one of which includes an exploration of religion and myth in the science fiction film, and another in cinema horror. He is currently writing a book, Sacred Terror: Religion and Horror on the Silver Screen, which is under contract with Baylor University Press, and due out next year. Doug made some time in his schedule to share his thoughts on horror movies and religion.

Doug Cowan: I was never really a fan of horror movies as a kid, though I devoured science fiction, and there is obviously considerable overlap. I have a vivid imagination, though, and I frighten rather easily, so I tended to be careful about what I watched. In 1966, for example, I watched the Star Trek pilot, “The Man Trap,” and was terrified by the salt-sucking creature. I still remember the smell of the E.W. Bickle Theatre in Courtenay, British Columbia, from the night I saw The Exorcist in 1973. Whenever I screen that film for a class now, I am taken right back to that night. Like most movie-goers, I leaped out of my seat during the chest-burster scene in Alien six years later, but I fell in love with Sigourney Weaver that night, so it kind of evened out. In many ways, I’m an unlikely candidate to write the book, but in other more significant ways, I think my own fears watching horror films have prepared me very well. That is, I want to understand my own fears as much as I do those of other people. I think the best scholarship is that which comes from some kind of personal investment.

That said, I did have a bit of an epiphany a couple of years ago. I was teaching in Missouri at the time, and one Sunday a local station ran a Hellraiser marathon. I’d never seen any of the films, though obviously I’d seen the covers in the video store. (Interesting how sci-fi and horror are almost always grouped side-by-side.) I decided to watch, and, I have to say, I was hooked—no pun intended. As I watched the Hellraiser mythology unfold, rather than the scared eight-year-old watching the salt-sucker try to drain Captain Kirk, the trained sociologist of religion began to make what I think are some rather significant connections. The moment of epiphany came during the fourth film, Hellraiser: Bloodline, which is, unfortunately, considered one of the poorest of the franchise, but which contains what I consider the quintessence of the relationship between cinema horror and religion. When the main character confronts Pinhead for the first time, he exclaims, “Oh my God!” To which Pinhead replies,

“Do I look like someone who cares what God thinks?”

And I thought, “But, of course.” And at that point, the basic structure for the book just fell into place. I began collecting horror films on DVD (a collection that runs to several hundred now—including both versions of The Exorcist and all the sequels), and reading just about everything written about horror and horror cinema (which is a surprising amount).

TF: I have had the privilege of seeing the outline for your book, and reading a draft of the Introduction and Chapter One. As I did several questions and thoughts came to mind. As we continue to lay a foundation before going into more depth on your book, what are some of the traditional perspectives you find about the relationship between religion and horror?

Doug Cowan: Quite apart from film studies, which asks a very different set of questions, the three most obvious perspectives are dismissal, theological, and psychological. That is, there are those who simply dismiss cinema horror as having any redeeming or revelatory value at all. There is very little one can say about these people, other than to point out that they are simply wrong—if for no other reason than that horror is one of the most robust and resilient of cinema genres. That doesn’t mean that every horror movie is worthwhile; many are appallingly bad. But as Ado Kyrou once said, “I urge you to look at ‘bad’ films; they are sometimes sublime.” It means, more importantly, that millions of people consume horror cinema, and we have to wonder about the attraction, about the need that is either reflected or filled by those products, about the fear these films reveal.

Others look at horror movies either through the lens of theological normativity or psychological dysfunction. The latter try to work out the psychological effects of horror films, often as a function of why people enjoy them so much, why they are one of the most resilient of all film genres. The former often impose their own theological categories onto horror films in an attempt to extract some wider moral or ethical significance from them, something that supports or reinforces the very categories they have imposed. Of course, this is what I am doing also, but from a very different perspective. I am a sociologist of religion and am less interested in why millions of people watch horror films (I take it as an obvious social fact that they do), than in the socially constructed fears that these films demonstrate.

TF: Why do you claim that there is an “inextricable relationship between religion and horror” that you develop in your book?

Doug Cowan: So many horror films start from the premise of the supernatural that to suggest they have nothing to do with religion is absurd. I remember reading a review of Rupert Wainwright’s Stigmata, for example, in which the reviewer began by commenting on how unusual it is to see religion and horror together. This just means that the person either hasn’t been paying attention, or has far too limited a view of what “religion” is. Of course, much of what I am proposing hinges on the definition of religion that informs the work. I take no theologically normative position, but take instead what I think is the very useful definition offered by William James in the third lecture of Varieties of Religious Experience: “the life of religion…is the belief in an unseen order, and that our supreme good lies in harmoniously adjusting ourselves thereto.” While this definition will obviously not suit a great many people, religious believers in p

articular, it has certain advantages for the sociologist. First, it avoids the problem of deity; some “unseen orders” posit a god, others many gods, others no god at all. This definition allows us to consider all visions of the unseen order on something approaching a level playing field. Second, and more importantly, it avoids what I call “the good, moral, and decent fallacy,” the historical and logical fallacy that religion is by definition a positive force in the lives of individuals or societies. When I say to someone, “John is a very religious person,” the likely inference will be that I mean you are moral, decent, upright—or at least you aspire to be on the basis of your religious beliefs. Now, I know this to be true of you as an individual, but there is very little historical evidence to support that it is true in all cases of religious belief. As you know, religion around the world and throughout time has been responsible for some of the most horrific atrocities in human history. Simply positing an “unseen order” avoids falling into the “good, moral, and decent” trap.

TF: I noted in the first chapter of your book that you reference a Christian missiologist who makes the unfortunate statment that “other than pornography, horror is the film genre least amenable to religious sensibilities.” Why do you find this all too common attitude reflected in people who might represent conservative expressions of more traditional religions? Is it a fear of horror somehow tearing down religion, or a fear of cultural decline through horror’s popularity?

Doug Cowan: This is precisely the problem of theological normativity closing down the vision with which one might look at the world around them. In many ways, conservative Christians (though they are hardly alone in this) live their lives enmeshed in a web of fears. This is implicit, for example, in my first two books, on the Christian countercult and on conservative reform movements in mainline Christianity. Fear drives the need to confront deviance and enforce conformity. It strikes me as absurd to think otherwise. Religion in the late modern period needs no help from horror films to do itself a disservice in any number of ways. Religious support for the war in Iraq, for example, is more horrifying to me than any horror movie. I think, though, that horror films (like some song lyrics) become a cheap and easy lightning rod to express one’s outrage, when there are far bigger, far scarier problems we can be concerned about. George Bush, for example, and his current World Tour of Terror, global warming, the possibility of nuclear war (whether driven by nation states or terrorist organizations), did I mention George Bush? I recall a poll conducted by a British horror magazine many years ago that said something like 37% of men would rather be trapped on a desert island with Freddy Krueger than with Margaret Thatcher. That said, I think that horror films are significant cultural artifacts that express what we are afraid of, not some sort of mind-control program valorising the acts we often see included in them.

TF: Wrapping up our foundation before moving to your book, why do you find conservative evangelicals so opposed to horror, often equating it with evil and the occult?

Doug Cowan: I go back the same answer. In the context of human religious experience and expression, it’s a very narrow, very restricted theological vision—one to which they are entitled, since it is their version of the “unseen order,” but narrow nonetheless. (I can see a number of readers spooling up Matt 7:13, as we speak!) The problem, though, comes when conservative Christians arrogate to themselves the right to act as moral, ethical, and theological arbiters for the rest of us—based solely on their interpretation of that unseen order. Returning to my point about living enmeshed in a web of fears, conservative Christians are an excellent example of the basic theoretical principle informing the book: sociophobics. That is, the principle that what we fear, how we fear, and how we are expected to act in the face of fear are socially constructed concepts. Of course, there are physical sensations that we share in common; of course, there are psychological aspects to fear. The problem is that studies have been limited to these, by and large. I am trying to broaden the playing field, to understand the relationship between religion and fear in a very different way.

As Petronius said, “It is fear that first brought gods into the world”—an insight that was explored in depth both by Rudolf Otto and Sigmund Freud, but which has, unfortunately, been ignored of late. A much more thorough exposition of the relationship between “Religion and Fear,” in fact, is the topic of the book I am planning while writing this one. In all kinds of ways, conservative Christians are taught to fear an amazing array for things, and have those fears reinforced in a striking variety of ways. Consider, for example, the Tennessee trial in the late 1980s, dubbed by the media “Scopes II.” That all started because a Tennessee housewife who spent a good portion of her time listening to fundamentalist Christian radio programming became terrified that “secular humanism”—that boogeyman of the New Age—had found its nefarious way into to the sanctuary of her daughter’s school.

Fascinating post.