It is a great privilege to read and reflect on horror in its multiple manifestations and layers of meaning. Not all of this is pleasant, but it is nevertheless enjoyable. This is the case with the book Horror Noire: Blacks in American Horror Films from the 1890s to Present (Routledge, 2011) by Robin R. Means Coleman. Coleman is Associate Professor in the Department of communication Studies and in the Center for AfroAmerican and African Studies at the University of Michigan.

It is a great privilege to read and reflect on horror in its multiple manifestations and layers of meaning. Not all of this is pleasant, but it is nevertheless enjoyable. This is the case with the book Horror Noire: Blacks in American Horror Films from the 1890s to Present (Routledge, 2011) by Robin R. Means Coleman. Coleman is Associate Professor in the Department of communication Studies and in the Center for AfroAmerican and African Studies at the University of Michigan.

A description of Horror Noire from the book’s back cover:

From King Kong to Candyman, the boundary-pushing genre of the horror film has always been a site for provocative explorations of race in American popular culture. In Horror Noire: Blacks in American Horror Films from 1890’s to Present, Robin R. Means Coleman traces the history of notable characterizations of blackness in horror cinema, and examines key levels of black participation on screen and behind the camera. She argues that horror offers a representational space for black people to challenge the more negative, or racist, images seen in other media outlets, and to portray greater diversity within the concept of blackness itself.

Horror Noire presents a unique social history of blacks in America through changing images in horror films. Throughout the text, the reader is encouraged to unpack the genre’s racialized imagery, as well as the narratives that make up popular culture’s commentary on race.

Offering a comprehensive chronological survey of the genre, this book addresses a full range of black horror films, including mainstream Hollywood fare, as well as art-house films, Blaxploitation films, direct-to-DVD films, and the emerging U.S./hip-hop culture-inspired Nigerian “Nollywood” Black horror films. Horror Noire is, thus, essential reading for anyone seeking to understand how fears and anxieties about race and race relations are made manifest, and often challenged, on the silver screen.

Robin R. Means Coleman discusses this book with TheoFantastique in the following interview.

TheoFantastique: Robin, thank you again for helping me secure a copy of the book for review, and for making time in an academic schedule for an interview. I was pleased to read in the Preface about your interest in horror, and to see the mention of Romero’s Night of the Living Dead, going back to your childhood. How did your childhood interests in horror combine with your academic explorations of the topic?

Robin R. Means Coleman: I am from Pittsburgh, which was not only home to George Romero and Tom Savini but, as you and your readers certainly know, the Pittsburgh area is the setting for the Night of the Living Dead and Dawn of the Dead films. The Dead films are fantastically political, and incredibly ideologically sophisticated. The films were my first textbooks, teaching me how to ask tough questions about race, class, and consumption. Only horror can interrogate such themes with real courage and honesty because the genre isn’t beholden to mainstream sensibilities.

Robin R. Means Coleman: I am from Pittsburgh, which was not only home to George Romero and Tom Savini but, as you and your readers certainly know, the Pittsburgh area is the setting for the Night of the Living Dead and Dawn of the Dead films. The Dead films are fantastically political, and incredibly ideologically sophisticated. The films were my first textbooks, teaching me how to ask tough questions about race, class, and consumption. Only horror can interrogate such themes with real courage and honesty because the genre isn’t beholden to mainstream sensibilities.

TheoFantastique: I think I’m fairly well read in the academic study of horror and genre films, but I don’t recall seeing much by way of a focus on an exploration of race. Is this an accurate understanding, and what drew you to focus on the unfortunate depiction of race, racism, and White vs. Black in much of horror cinema?

Robin R. Means Coleman: Actually, there are several great scholarly articles out there on Blacks in horror films by folks like Harry Benshoff, Frances Gateward, and Ellen Scott. But, as far as I know, no one has attempted to take on a book-length, full history—from the 19th century to present — of Blacks’ participation in American horror films. Though an academic book, I wanted to be respectful of this fun, evocative genre by not sucking the life out of it with overly puffed up academese.

I wrote the book because there are two themes which emerge about Blacks’ participation in horror. The first theme focuses on unfortunate depictions. This includes an obsession with Blacks as savage jungle dwellers practicing voodoo while placing White women in peril. Think: King Kong or Black Moon. I discuss these films, and a host of others, in the book. In addition, I specifically cite the 1931 film Ingagi as one of the most grotesque films ever made for its disgusting treatment of Blacks. Ingagi was promoted as a real-life documentary (it really wasn’t) about Blacks in the Congo who engaged in bestiality and even procreated with apes. The film featured an actor in an ape costume and was shot in a zoo in L.A. Still, people believed it that the film was absolutely true. It was devastating to race relations.

The second theme I present in the book is one about empowerment, unity, and camaraderie. Horror is one of the few genres that has the capacity of shun stereotypes and clichés. This means we can get beyond stereotype spotting, and focus on the innovative representations. There are horror films, like Welcome Home Brother Charles which is an indictment against police brutality and the notion of the hypersexual Black man. Charles is a Black man who takes out rogue cops with his penis! Another example of more empowering films are Hellbound Train, Go Down Death, Def by Temptation, or Tales from the Hood that offer inspiring lessons on protecting Black communities from drugs, gangs, and other “sins,” while valuing Black life. Horror films such as Kracker Jack’d expose Black-on-Black or intraracial strife, like calling one another the n-word or dismissing someone for not being “Black enough,” while presenting a message of unity. There are horror films with integration themes like Omega Man. And, then there are the horror films that are cool because they are simply horror—no more, no less—like Holla, The Embalmer, or The Final Patient. The point is, horror has shown it can be trailblazing in its treatment of Blacks.

The second theme I present in the book is one about empowerment, unity, and camaraderie. Horror is one of the few genres that has the capacity of shun stereotypes and clichés. This means we can get beyond stereotype spotting, and focus on the innovative representations. There are horror films, like Welcome Home Brother Charles which is an indictment against police brutality and the notion of the hypersexual Black man. Charles is a Black man who takes out rogue cops with his penis! Another example of more empowering films are Hellbound Train, Go Down Death, Def by Temptation, or Tales from the Hood that offer inspiring lessons on protecting Black communities from drugs, gangs, and other “sins,” while valuing Black life. Horror films such as Kracker Jack’d expose Black-on-Black or intraracial strife, like calling one another the n-word or dismissing someone for not being “Black enough,” while presenting a message of unity. There are horror films with integration themes like Omega Man. And, then there are the horror films that are cool because they are simply horror—no more, no less—like Holla, The Embalmer, or The Final Patient. The point is, horror has shown it can be trailblazing in its treatment of Blacks.

TheoFantastique: What are some of the earliest representations of the connections of various fears to Blacks in horror?

Robin R. Means Coleman: I trace the Black boogeyman back to 1915 with Gus in The Birth of a Nation. Gus is the unbridled Black male in the film who obsessively pursues a young White girl. She is so sickened and terrified by Gus that she throws herself off of a cliff, and to her death, to save herself from Gus who is depicted as grotesque and utterly repulsive. By way of comparison, Frankenstein’s Monster is similarly grotesque, but we are moved to feel sorry for him. When Frankenstein’s Monster accidentally kills the little girl he is playing with, we feel just as bad for him as we do for her. That isn’t the case with Gus. He is so monstrous that the audience is asked to side with the KKK in its hate for such a creature. The horror genre constantly reinvents Gus. You see him in a range of movies from King Kong to Candyman. Gus as a horror figure is even traded on in political campaign ads like the infamous Willie Horton commercial. Gus gives rise to the brutal buck stereotype, and unfortunately that stereotype is still with us in horror and beyond.

TheoFantastique: I was interested in your mention of the enjoyment of horror in the Black community for many years. Why do you think there is strong connection to horror in the Black community, particularly when negative representations of Blacks have been so prevalent in the genre?

Robin R. Means Coleman: Initially, the book was also going to include interviews with Black viewers about their experiences with the horror genre. When I would ask about horror viewing, many Blacks would declare that they never watch horror: “too demonic” was often the reason for swearing off the genre. Then, they would proceed to recount the plots of dozens upon dozens of horror films that scared them! Night of the Living Dead, Blacula, Sugar Hill, I Am Legend, Blade, Candyman, Michael Jackson’s Thriller, nearly every Vincent Price scary movie, the comic horror films like Abbott and Costello meet Frankenstein…these were all cited as popular films among Blacks. My research reveals that films like these were less expensive to acquire for “nabe” or neighborhood theaters located in Black communities. More, the Black press had a hand in promoting films that included Black characters. Though the Black characters were at times stereotypical, sometimes the press celebrated the fact that the rare Black face could be seen on the big screen. Then, Black audiences worked to see moments of resistance — a fighting back against the stereotypes — embedded in the performances. However, with films like Blacula, which directly disparages racism and the slave trade, it is clear why such a film could be popular among Black audiences, even if cheaply made. More mainstream films simply don’t have the courage. For example, films such as Mississippi Burning or a Time to Kill deal with race hatred, but they become these odd ‘White savior’ films. Outside of horror, for example, Will Smith portrays a self-sacrificing ghost/caddy in service to Matt Damon’s character in The Legend of Bagger Vance. Michael Clarke Duncan is similarly sacrificing in the supernatural film The Green Mile.

Robin R. Means Coleman: Initially, the book was also going to include interviews with Black viewers about their experiences with the horror genre. When I would ask about horror viewing, many Blacks would declare that they never watch horror: “too demonic” was often the reason for swearing off the genre. Then, they would proceed to recount the plots of dozens upon dozens of horror films that scared them! Night of the Living Dead, Blacula, Sugar Hill, I Am Legend, Blade, Candyman, Michael Jackson’s Thriller, nearly every Vincent Price scary movie, the comic horror films like Abbott and Costello meet Frankenstein…these were all cited as popular films among Blacks. My research reveals that films like these were less expensive to acquire for “nabe” or neighborhood theaters located in Black communities. More, the Black press had a hand in promoting films that included Black characters. Though the Black characters were at times stereotypical, sometimes the press celebrated the fact that the rare Black face could be seen on the big screen. Then, Black audiences worked to see moments of resistance — a fighting back against the stereotypes — embedded in the performances. However, with films like Blacula, which directly disparages racism and the slave trade, it is clear why such a film could be popular among Black audiences, even if cheaply made. More mainstream films simply don’t have the courage. For example, films such as Mississippi Burning or a Time to Kill deal with race hatred, but they become these odd ‘White savior’ films. Outside of horror, for example, Will Smith portrays a self-sacrificing ghost/caddy in service to Matt Damon’s character in The Legend of Bagger Vance. Michael Clarke Duncan is similarly sacrificing in the supernatural film The Green Mile.

TheoFantastique: You speak positively in the book about George Romero breaking through the problem of race in horror through his zombie films. Can you speak to what you see as his positive contribution here?

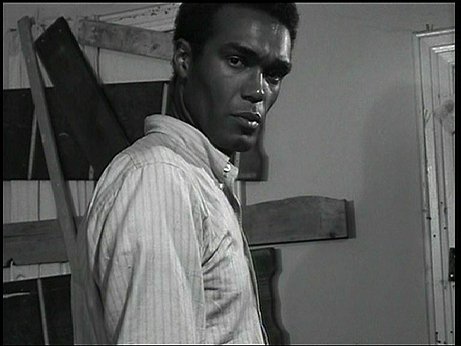

Robin R. Means Coleman: Indeed, Romero and his crew are presented as revolutionaries in the book. I have the greatest respect for what Romero has accomplished with Night of the Living Dead, and then with Dawn of the Dead. You see, much of the 1950s and 1960s, before Night, as it pertains to Blackness, horror hit a bit of a low. There were the science-fiction themed films of the 1950s in which no one could image Blacks (or White women for that matter) competently working in laboratories. Films like The Giant Claw and The Alligator People render Blacks nearly invisible, and that goes on for much of the decade. Spider Baby kills off a deliveryman played by Mantan Moreland in its first minutes. This is pretty much Blacks’ existence in horror in the 1950s and 1960s. They are either comic relief or are rendered invisible, that is, until Night of the Living Dead which presents a Black man—Ben — in a serious, complex, dramatic role. Before Ben, Blacks simply were not depicted as smart and, absent voodoo, they could not be resourceful (for example, could the Haitian people in The Serpent and the Rainbow be powerful without voodoo). It is important to remember that Romero was driving his film to New York for distribution on the day of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination. That was a real life reminder of how intent society was on limiting Blacks’ status. Hence, Ben was behaving on the big screen in a way that some Blacks in real life could not. In Dawn, Romero depicts the Black SWAT officer, Peter, as surviving the zombies alongside a very pregnant White newscaster, Francine. A great number of films before Dawn exploited fears of miscegenation. But Romero didn’t go that route. Working against the conventions of social fears was truly heroic. I think Romero showed image-makers across genres what is possible in how to write a human story. I just wish more filmmakers would pay attention.

TheoFantastique: You discuss Black-produced horror films. How have these helped express forms of horror that articulate Black fears and social issues?

TheoFantastique: You discuss Black-produced horror films. How have these helped express forms of horror that articulate Black fears and social issues?

Robin R. Means Coleman: In Horror Noire, I give significant attention to horror films made for and by Blacks. One thing that Black filmmakers tend to have in common is a theme of religiosity and redemption. The films of Eloyce Gist, Spencer Williams, James Bond III all focused on succumbing to temptation, sin, and the struggle for salvation. They all root their stories in the history of the Black southern Christian church. The fear is falling into wickedness. You see similarly themed movies coming out of Nigerian Hollywood or “Nollywood,” and in Tyler Perry films. The cautionary tale is universal.

Rusty Cundieff as director of Tales from the Hood and Snoop Dog as producer and star of Hood of Horror extend these religious themes by going beyond stories of saving individual souls. They exploit fears of being labeled a sell out to your community. You can imagine what happens to the Black cop who keeps quiet about White police brutality, or the Black guy who works on the political campaign of a White supremacist, or the Black guys selling drugs in the ‘hood. These actions are all depicted as the ultimate sins, from which there can be no redemption. In short, these movies say that the thing that Blacks fear most is discrimination, inequality, and actions that keep their communities from thriving.

TheoFantastique: With the changes of depictions of Blacks vs. Whites in horror as the genre has developed, what do you see the future holding in this area?

Robin R. Means Coleman: Like any other genre, horror presents great diversity in form and quality. Some films are craptastic, some are wholly entertaining, and some are really smart and inspiring…some are all three simultaneously! Today, the genre displays a keen self-awareness of its past, as evidenced by the Scream and Scary Movie franchises. Horror continues to get smarter as it moves beyond negative stereotypes. Now, horror tales are not obsessively pitting Whites against Blacks over fears of integration or miscegenation. What you see at present are diverse, interracial teams fighting vampires or zombie-making plagues (e.g., Dracula 2000 or almost anything with the rapper/actor Coolio in it). Good horror does not sugar coat our social quandaries. Good horror is going to be honest about the fact that we are all not gathered ‘round singing Kumbayah. Really good horror is going to be imaginative in how it portrays evil. The future of horror will rise and fall on filmmakers’ imagination. But, if we keep being subjected to remakes and “reimaginings” — the genre is, regrettably, going to become stale.

TheoFantastique: Robin, again, thank you for this interview, and for a great book that explores an uncomfortable topic.

Robin R. Means Coleman: And thank you for letting me share. I want to impress upon your readers that the book is an interesting read, and while it exposes some poor treatments, it is not an uncomfortable read. I believe it will be a fun and enjoyable exploration for any fan of the horror genre!

Horror Noire can be purchased from the TheoFantastique Store.

2 Responses to “Interview with Robin R. Means Coleman on Horror Noire: Blacks in American Horror Films from the 1890s to Present”