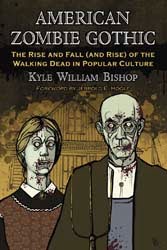

I first became aware of Kyle Bishop and his work on zombies in film and culture for his PhD while researching the surge in academic work on horror. I then came across an article on his research in The University of Arizona’s UA News, “The Zombie: A New Monster for a a New World.” I soon learned thereafter that Bishop had modified his PhD work for the book American Zombie Gothic (McFarland, 2010). This book provides a fascinating exploration of the zombie in culture, from its early expressions in literature and horror films to more recent expressions in the zombie explosion. Bishop teaches at Southern Utah University and carved out some space to discuss his book.

I first became aware of Kyle Bishop and his work on zombies in film and culture for his PhD while researching the surge in academic work on horror. I then came across an article on his research in The University of Arizona’s UA News, “The Zombie: A New Monster for a a New World.” I soon learned thereafter that Bishop had modified his PhD work for the book American Zombie Gothic (McFarland, 2010). This book provides a fascinating exploration of the zombie in culture, from its early expressions in literature and horror films to more recent expressions in the zombie explosion. Bishop teaches at Southern Utah University and carved out some space to discuss his book.

TheoFantastique: Kyle, thanks for squeezing an interview in with your busy teaching schedule. I know that your research in zombies began with your PhD dissertation work. Can you tell me how you developed the personal interest in this subject matter, and how you convinced your academic institution to support this kind of dissertation research?

Kyle Bishop: No problem—I always appreciate the opportunity to talk about my research! My academic interest in zombie movies began about six or seven years ago. I was having lunch with Dr. Todd Petersen, another English professor at Southern Utah University, and we were riffing on an Eddie Izzard bit about how car chases don’t appear in books. We were trying to come up with other thematic tropes and scenes that only really exist on the screen, for whatever practical or aesthetic reason. At the time, almost no literary zombie narratives existed, and I started to wonder where the damn subgenre came from in the first place. This conversation lead me to research Haitian folklore and voodoo, to view early zombie movies like White Zombie (Halperin, 1932), and to examine Night of the Living Dead (Romero, 1968) with a much more critical eye. A couple of years later, my first article, “Raising the Dead: Unearthing the Nonliterary Origins of Zombie Cinema” appeared in the Journal of Popular Film and Television (33.4).

At about the same time, I was entering the University of Arizona as a graduate student in the English program. My interest in zombie cinema had continued to grow, and with a few academic conferences under my belt, I decided to pitch the idea of a zombie-themed dissertation to the graduate director, Meg Lota Brown. Already having a scholarly publication on the subject certainly helped me and my cause, but I also made a strong case about the cultural and critical significance of the subgenre to American culture. Luckily, Dr. Brown and others, such as Dr. Jerrold Hogle and my eventual dissertation director Dr. Susan White, recognized how cinema is just another form of literature, and they wholeheartedly endorsed my proposal. The academic landscape is changing, you see, and what constitutes “fine art” and “canonical literature” is shifting as well—there is now a place for popular culture in the academy.

TheoFantastique: In the Introduction to your book you mention the significance of elements of pop culture as a barometer for measuring our cultural anxieties. How do zombie films and other expressions of these creatures function in this way in relation to our post-9/11 environment with its strong sense of apocalyptic dread?

Kyle Bishop: Even a cursory glance at a list of horror films by year of release reveals some marked tendencies—as David J. Skal points out in The Monster Show (Faber & Faber 2001), horror film production increases during times of social stress, such as the Depression-era 1930s and the Vietnam-laden ’60s and ’70s. The Hollywood market since September 11, 2001, has been flooded with horror films, most notably remakes of films from the 1970s, and one of the most prolific of subgenres has been the zombie invasion narrative. In a nutshell, death, terrorist attacks, and general warfare make us unavoidably aware of our own mortality and our lack of national security and supremacy. As a survival mechanism, then, our popular culture fights back, purging our minds and souls of these fears and anxieties by depicting infinitely more horrific scenarios on the screen. Through the ancient practice of catharsis, we feel better about our lives after watching a zombie movie—after all, things may be bad, but our entire societal infrastructure hasn’t collapsed, we are still alive, and the dead continue to rest in peace. Zombie movies also allow us to fulfill certain survivalism fantasies, the ideal that if things really did fall apart around us, we would be able to survive because of our cunning, our planning, and our guns. Despite the blood and gore, it’s all very empowering.

Kyle Bishop: Even a cursory glance at a list of horror films by year of release reveals some marked tendencies—as David J. Skal points out in The Monster Show (Faber & Faber 2001), horror film production increases during times of social stress, such as the Depression-era 1930s and the Vietnam-laden ’60s and ’70s. The Hollywood market since September 11, 2001, has been flooded with horror films, most notably remakes of films from the 1970s, and one of the most prolific of subgenres has been the zombie invasion narrative. In a nutshell, death, terrorist attacks, and general warfare make us unavoidably aware of our own mortality and our lack of national security and supremacy. As a survival mechanism, then, our popular culture fights back, purging our minds and souls of these fears and anxieties by depicting infinitely more horrific scenarios on the screen. Through the ancient practice of catharsis, we feel better about our lives after watching a zombie movie—after all, things may be bad, but our entire societal infrastructure hasn’t collapsed, we are still alive, and the dead continue to rest in peace. Zombie movies also allow us to fulfill certain survivalism fantasies, the ideal that if things really did fall apart around us, we would be able to survive because of our cunning, our planning, and our guns. Despite the blood and gore, it’s all very empowering.

TheoFantastique: Fans of the current forms of zombies may forget the very different type of zombie portrayed in films in the first decades of the twentieth century. What were the early sources for this unique New World monster, how were they portrayed in early literature and film, and what types of cultural elements did they symbolize?

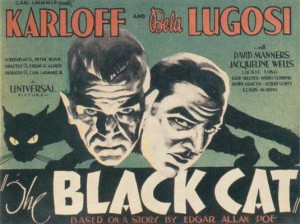

Kyle Bishop: Pretty much all of the zombie narratives prior to Night of the Living Dead played on the trope of the voodoo zombie; that is, a dead (or in some cases, hypnotized) body reanimated through magical or scientific means to function as a slave, servant, or soldier. Early literary examples are few and always presented as nonfiction ethnographical reports, the most famous being William Seabrook’s The Magic Island (Harcourt Brace, 1929). These accounts sensationalize the mysterious and pagan practices of exotic locales such as Haiti, and they mostly function to foment racism and imperialist paranoia. The early films are little better—the zombies are either dark-skinned minions or violated white women. In either case, the zombie acts as an essentially racist manifestation of the West’s greatest fear: that those native peoples once colonized and killed by imperialist expansion will one day rise up and slaughter their white oppressors. During the ’40s and ’50s, the zombie often mutated into the tool of a mad scientist or an invading alien race (most ignominiously in Ed Wood’s Plan 9 from Outer Space [1959]), but the core theme remains the same: fear of conquest and enslavement.

Kyle Bishop: Pretty much all of the zombie narratives prior to Night of the Living Dead played on the trope of the voodoo zombie; that is, a dead (or in some cases, hypnotized) body reanimated through magical or scientific means to function as a slave, servant, or soldier. Early literary examples are few and always presented as nonfiction ethnographical reports, the most famous being William Seabrook’s The Magic Island (Harcourt Brace, 1929). These accounts sensationalize the mysterious and pagan practices of exotic locales such as Haiti, and they mostly function to foment racism and imperialist paranoia. The early films are little better—the zombies are either dark-skinned minions or violated white women. In either case, the zombie acts as an essentially racist manifestation of the West’s greatest fear: that those native peoples once colonized and killed by imperialist expansion will one day rise up and slaughter their white oppressors. During the ’40s and ’50s, the zombie often mutated into the tool of a mad scientist or an invading alien race (most ignominiously in Ed Wood’s Plan 9 from Outer Space [1959]), but the core theme remains the same: fear of conquest and enslavement.

TheoFantastique: The most popular forms of the zombie today was created by George Romero in his Night of the Living Dead. What types of influences came together for Romero to create a different expression from the past, and what types of cultural anxieties were reflected in his 1968 film?

Kyle Bishop: Ironically enough, Romero wasn’t trying to invent a new form of zombie when he made his low-budget horror movie; in fact, he was attempting to adapt Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend (Walker & Co., 1954) in a rural Pennsylvanian setting. However, I argue that no adaptation really functions as a one-to-one formula; Romero was also clearly influenced by other landmark horror films as well, most notably Invasion of the Invasion of the Body Snatchers (Siegel, 1956), The Birds (Hitchcock, 1963), and The Last Man on Earth (Ragona and Salkow, 1964), itself an adaptation of Matheson’s novel. At the same time, Romero’s film was reacting (either consciously or unconsciously) to his contemporaneous world’s anxieties concerning the escalating war in Vietnam (most notably the disaster of the Tet Offensive), the degradation of the traditional nuclear family, and the tensions associated with the Civil Rights Movement. The latter is perhaps the most poignant; even though Romero has repeatedly insisted the role of Ben was not overtly intended for a black actor, Duane Jones’ race nonetheless dramatically influences the way we receive and respond to the film, especially today. I mean, the movie is essentially about a black man who stands up to a group of white people, causes them all to be killed, and is brutally lynched by a white posse at the end of the film. The zombies hardly seem relevant at that point.

Kyle Bishop: Ironically enough, Romero wasn’t trying to invent a new form of zombie when he made his low-budget horror movie; in fact, he was attempting to adapt Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend (Walker & Co., 1954) in a rural Pennsylvanian setting. However, I argue that no adaptation really functions as a one-to-one formula; Romero was also clearly influenced by other landmark horror films as well, most notably Invasion of the Invasion of the Body Snatchers (Siegel, 1956), The Birds (Hitchcock, 1963), and The Last Man on Earth (Ragona and Salkow, 1964), itself an adaptation of Matheson’s novel. At the same time, Romero’s film was reacting (either consciously or unconsciously) to his contemporaneous world’s anxieties concerning the escalating war in Vietnam (most notably the disaster of the Tet Offensive), the degradation of the traditional nuclear family, and the tensions associated with the Civil Rights Movement. The latter is perhaps the most poignant; even though Romero has repeatedly insisted the role of Ben was not overtly intended for a black actor, Duane Jones’ race nonetheless dramatically influences the way we receive and respond to the film, especially today. I mean, the movie is essentially about a black man who stands up to a group of white people, causes them all to be killed, and is brutally lynched by a white posse at the end of the film. The zombies hardly seem relevant at that point.

TheoFantastique: How did the zombie shift in its conceptualization from a symbol of colonialism and racism to a critique of the nuclear family, consumerism, and class warfare in some of its more recent manifestations?

Kyle Bishop: Contemporary relevance sells, and by 1968, the United States viewing public just wasn’t that interested in imperialism (although well into the 1970s, Italy was making voodoo-themed zombie movies, just to illustrate the different Zeitgeists). Instead, Romero and his imitators drew on what seemed to really matter at the given moment: Vietnam, interracial relationships, suburbanization, economic excess and conspicuous consumption, and the Cold War. The economic climate of the ’70s made Dawn of the Dead (Romero, 1978) extremely topical and powerful (although it still explores issues of racism, racial tension, and—at least allegorically—imperialism), and the Cold War tensions set the stage for the militarized bunker of Day of the Dead (Romero, 1985). However, the social, economic, and political climate of the 1980s grew a bit too stable and comfortable to support any serious attempts at zombie narratives—the only films that had any kind of financial success were lowbrow comedies like Return of the Living Dead (O’Bannon, 1985). The 1990s were even more barren, although New Zealand produced the raucous comedy Dead Alive (Jackson, 1992). It took the combined resurgence of unexpected terrorist attacks, two foreign wars, a financial collapse, and multiple pandemics to bring the zombie back to the forefront as a topical and relevant allegory.

TheoFantastique: You refer to our time as a “Zombie Renaissance.” What kind of cycle has the zombie gone through in culture, and why might our time be understood as going through a Zombie Renaissance? Why is this monster functioning so frequently as our primary creature to express our fears?

Kyle Bishop: As I’ve illustrated, zombie movies, like all good horror narratives, ebb and flow depending on the greater cultural consciousness. They were big in the 1930s, again in the ’70s, and, almost like clockwork, they are back today. There was a time when a “good” year would see five or six zombie movies; in recent years, we’ve seen dozens and dozens in a single year. Now, a lot of that increase in production can simply be tied to the overall increase in film production—especially independent and online film production—we are seeing worldwide, but of late zombie narratives have been rivaling those of vampires in number. Why? Because we all have apocalypse on the brain right now. Thanks to the “War on Terror,” we have all been conditioned to believe that the world can end at any moment, be it a result of a dirty bomb, a hijacked nuclear weapon, or an anthrax attack. Hell, even Mother Nature is out to get us with hurricanes, global warming, the avian flu, and the H1N1 virus. Survivalist handbooks are all-time bestsellers right now, so why should we be surprised the Zombie Survival Guide (Brooks, 2003) is a bestseller as well? I’ve heard recently that some governments are event funding the drafting of official zombie outbreak strategies! Because we fear the destruction of our cities, because we fear the death of our loved ones, because we fear the invasion of unwanted masses across our borders, and because we fear the end of civilization as we know it, the zombie invasion narrative becomes the great cathartic panacea. No one creature or horror subgenre fulfills so many subconscious needs in one fell swoop like the zombie.

Kyle Bishop: As I’ve illustrated, zombie movies, like all good horror narratives, ebb and flow depending on the greater cultural consciousness. They were big in the 1930s, again in the ’70s, and, almost like clockwork, they are back today. There was a time when a “good” year would see five or six zombie movies; in recent years, we’ve seen dozens and dozens in a single year. Now, a lot of that increase in production can simply be tied to the overall increase in film production—especially independent and online film production—we are seeing worldwide, but of late zombie narratives have been rivaling those of vampires in number. Why? Because we all have apocalypse on the brain right now. Thanks to the “War on Terror,” we have all been conditioned to believe that the world can end at any moment, be it a result of a dirty bomb, a hijacked nuclear weapon, or an anthrax attack. Hell, even Mother Nature is out to get us with hurricanes, global warming, the avian flu, and the H1N1 virus. Survivalist handbooks are all-time bestsellers right now, so why should we be surprised the Zombie Survival Guide (Brooks, 2003) is a bestseller as well? I’ve heard recently that some governments are event funding the drafting of official zombie outbreak strategies! Because we fear the destruction of our cities, because we fear the death of our loved ones, because we fear the invasion of unwanted masses across our borders, and because we fear the end of civilization as we know it, the zombie invasion narrative becomes the great cathartic panacea. No one creature or horror subgenre fulfills so many subconscious needs in one fell swoop like the zombie.

TheoFantastique: I was surprised to read of your inclusion of zombies within the Gothic tradition. How do you see zombies fitting within this classification?

Kyle Bishop: At their most fundamental level, I don’t see the zombie monsters themselves as Gothic inventions. As much as some people would wish it, the zombie can never be a romantic figure like Count Dracula or Lestat—a dead creature with no higher brain functions just isn’t going to work that way unless the protocols of the subgenre are irrevocably violated. However, the stories zombies make possible are overtly Gothic in nature, particularly in their settings and locales. Like so many Gothic novels of the nineteenth century, zombie narratives are often stranded in a fixed location, a “haunted house” (or mall or bunker or mortuary or apartment building or pub) that symbolizes the fears, anxieties, and secrets of a lost era. Zombie narratives assault their protagonists—and by extension, their audiences—with counterfeit representations of things that are hollow, lost, and ultimately unfulfilling (according to Hogle’s conception of the Gothic); that is, the mall offers no consumer comforts (and never did), the bunker offers no safety (and never did), and your loved ones aren’t really back from the dead—they are just dead (and always were). In many ways, then, zombie narratives are substantially more Gothic than films like Twilight (Hardwicke, 2008) ever could be.

TheoFantastique: Given the international challenges we face in the twenty-first century, do you see the zombie continuing to function as a major monstrous figure alongside those of European derivation, and is the zombie perhaps better suited to express our cultural anxieties at this time?

Kyle Bishop: Two or three years ago, I would have said the zombie was played, that it was burning out and disappearing. We had a lull in production, and the films we were getting were all sequels and unoriginal remakes. Now I’m not so sure. The comedic zombie films (the “zombedies”) are getting increasingly clever and even poignant, more and more books and literary zombie narratives are being written, and we are finally going to see our first zombie television series: AMC’s The Walking Dead (Darabont, 2010). I now think the zombie has finally paid its dues—cut its teeth, as it were—and joined the venerable pantheon of Gothic and European monsters. Instead of using the zombie to adapt to new social and cultural tensions and anxieties, I expect enterprising authors and filmmakers will now adapt the zombie to fit their projects, to meet their needs. As far as I can tell, the zombie is here to stay.

TheoFantastique: Kyle, thank you again for making the time to discuss your great book. I hope this research project continues.