Doug Cowan participated in one of this blog’s more popular interviews in the past that dealt with issues surrounding terror and religion that he deals with in his forthcoming book Sacred Terror: Religion and Horror on the Silver Screen. Although Doug has a very busy academic schedule, he has come back for a second time to share some thoughts related to one of his book’s chapters that I had the privilege of previewing.

Doug Cowan participated in one of this blog’s more popular interviews in the past that dealt with issues surrounding terror and religion that he deals with in his forthcoming book Sacred Terror: Religion and Horror on the Silver Screen. Although Doug has a very busy academic schedule, he has come back for a second time to share some thoughts related to one of his book’s chapters that I had the privilege of previewing.

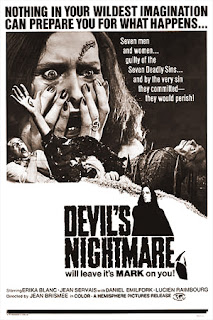

TheoFantastique: Doug, thanks for being willing to sit in the interview chair again for further discussion on your book. Thanks too for allowing me the privilege of reviewing the drafts of the chapters. The book is great, and it will make for a wonderful contribution to the academic exploration of religion and horror. I’d like to ask a few questions that arise out of Chapter 7, “The Unholy Human: Fear of Fanaticism and Fear of the Flesh.” You begin this chapter with a discussion of two films, Cult of Fury and The Devil’s Nightmare. From these you move to discuss how “cinema horror to prime-time television, [and] popular entertainment [have] contributed to reinforcing the sociophobic of religious fanaticism and the dangerous religious Other.” Can you share an example of how this has taken place in regards to some of the new religions have been treated in this fashion, and how this is reinforced and played out in horror films?

Doug Cowan: It’s my pleasure to be back again. As I’ve told a lot of people, yours is the only blog I read with any regularity. And glad you like the book. I’m certainly looking forward to seeing it out.

In terms of your question, which is an important one, the issue of popular entertainment as cultural reinforcement seems key to me. Consider, for example, any number of Law and Order episodes that are advertised as “ripped from the headlines”—though they almost inevitably also include an oxymoronic disclaimer that there is not meant to be any correlation between the show’s narrative, characters, and action and real people or real events. It’s a patent falsehood, of course, because the producers of the show are counting on viewers resonating with precisely those events on which episodes are based in order to secure their audience share. The same holds true for other aspects of popular entertainment, and the issue, to put it one way, is concision: how quickly, and with how little effort, can we convey the central sense of threat, of dread, or of danger? That is, what is the minimum amount of information we have to include before we can move on to the characters in the series saving the day?

In terms of new religious movements—or any religion, really—three things are significant here: a basic religious illiteracy that is pandemic in our society; the sociophobic power of the word “cult”; and three decades of media stigma and stereotyping that has contributed to both of these.

First, the appalling religious illiteracy with which this country (and mine) is bedeviled—and which Steve Prothero points out so devastatingly in his new book—means that the vast majority of viewers are simply not equipped to tell where the “real life events” end and the commercially produced fantasy begins. If this lack of basic information and understanding is true for the dominant religious tradition and its participants (which is Prothero’s point), how much more true must it be for marginalised or stigmatised religious traditions about which people are already primed to believe the worst? People who watch The Exorcist or The Craft—the former allegedly based on a true story, the latter which had a real Witch as a consultant on the production—cannot discern which are the “real bits” and which are pure Hollywood. In The Craft, actual lines from the First Degree Initiation into Gardnerian Wicca is mixed with more sensationalised action sequences. The problem is that many people seem unable (or unwilling) to make adequate distinctions between these, and this is something filmmakers can exploit. Indeed, when I was researching Cyberhenge, my book on modern Pagans and the Internet, I followed numerous online discussions in which those who want to be (or claim to be) Wiccans or Witches ask each other whether they’ve been able to manifest the powers they saw on The Craft or the latest episode of Charmed. I even remember one online conversation in which one of the participants was outraged at the suggestion that the spells used in Harry Potter were not real and would not work for her.

Second, there is the sociophobic power of the word, “cult.” As I say in the chapter you’re referring to, in late modern society, few labels function so effectively as a lightning rod for the fear of fanaticism and the often terrifying power of religion. Indeed, this is part of the reason behind the book that David Bromley and I have just published, entitled Cults and New Religions: A Brief History—to point out that there is far, far more to these groups than the controversies that brought them to public attention. Though there are, literally, thousands of new, alternative, and non-traditional religious groups and movements in North America, Europe, and Asia—the vast majority of which pass largely unnoticed by wider society—two comparatively isolated themes have come to dominate popular discourse about them: control and violence. Of these, the former is lodged in concerns about “brainwashing” and “cult mind control,” while the latter lives in recurring fears over the possibility of religiously motivated mass suicides, ritual murder, violent confrontation with civil authority, or even the potential for attacks on civilian populations—all represented iconographically through groups such as Peoples Temple, the Branch Davidians, the Order of the Solar Temple, Aum Shinrikyo, and Heaven’s Gate. Though the now voluminous social scientific literature on new religions demonstrates that there is little if any credible evidence for “brainwashing,” and that, when we consider the sheer number of new religious movements involved, instances of violence are extremely rare, panic over the power of religion to motivate antisocial behavior thrives just below the cultural surface, continually reinforced by a wide range of media products. All a newspaper or broadcast report has to do is use the word “cult” and all manner of negative associations are immediately mobilised.

Which brings us to the third point. In terms of new religions, popular entertainment has three decades of really problematic journalism to r

ely on for preparing the ground. For a wide variety of reasons—including editorial position, the time constraints of news production, the lack of education many reporters have in religion of any kind, and the need to connect with the extant prejudices of their target audience—reporting when it comes to new religions has been appalling to say the least. I remember one reporter calling me for an interview. He wanted to do a “light, humourous, offbeat piece about these wacky cults people join—you know, like Jonestown and Heaven’s Gate!” The fact that Jonestown is a place not a group, I reminded him that nearly a thousand people died in those two incidents, and that I found his attitude deeply offensive. Needless to say, the interview was off…

This is not to say that new religions don’t get played for laughs, though the humour seems a bit black to me at times. In The Simpsons episode in which the family joins a group called the Movementarians, the portrait of the leader is clearly a caricature of L. Ron Hubbard, while the leader driving through the fields in a Rolls as his followers toil in the dirt is a reference to Baghwan Shree Rajneesh. The third episode of Family Guy has Meg join a group that is based almost entirely on Heaven’s Gate, while a number of episodes of South Park have dealt with new religious movements—most notably, perhaps, the Church of Scientology.

In terms of cinema horror, though, the important point to note—and this is also true for the television dramas and comedies—is that the fear of new religions is deeply enough embedded that very little explanation is needed to communicate what the audience is meant to perceive as the threat. You simply need to use the word “cult,” or make unambiguous reference to well-known incidences of new religions and violence.

TheoFantastique: In this chapter you discuss a number of films with satanist elements that usually include secret societies engaged in evil. I recall watching a number of these as a teenager, usually those produced by Hammer Films. Can you touch on the sociophobic that undergirds such films, where the popular mythology that informs the portrait of such groups comes from, and to what extent these things influenced the satanic panics of the 1980s and 1990s, and may still be subtly influential today?

Doug Cowan: In some cultural domains, I’m not convinced the influence of these beliefs is so subtle. It’s also important to point out that there are satanically-oriented films, and then there are those that have no satanic connection at all, but which are presented that way either through the ignorance of the characters in the film (which is later dispelled, as in The Believers) or the more general fear of these groups extant in the so-called “satanic panics.”

There are a number of things working here as well, I think. First, in terms of the satanic coven, the secret group, the evil cabal, there is a history that is many hundreds of years old feeding the fear exploited by cinema horror. The association of witches with Satan goes back at least a thousand years in the Christian church—though the tenor of that association shifts depending on where you are and when—and there is a fund of popular “knowledge” about such things as the Witch hunts, the Inquisitions, the Witch trials that filmmakers draw on. Once again, though, they are counting on both the willingness of audiences to accept dramatic license with these events, and the general ignorance of those audiences about what actually happened. Though modern Pagans, for example, have worked diligently to dispel the association of Wicca and Witchcraft with satanism, the connection is still made quite regularly in the media. We go back to the issue of religious illiteracy: since few people, relatively speaking, know very much about either modern Paganism or Satanism, they are not in a position to discriminate between them, and so, very often, they simply don’t. They accept one as the other, whether there is any logical connection or not. This is exactly the kind of fear that is fed by satanic panics—and by spiritual entrepreneurs like Malachi Martin and Bob Larson, whose livelihoods depend on stoking the fires, as it were. Books like Martin’s Hostage to the Devil, and Larson’s long-running crusade against all things demonic receive far more popular attention than the efforts of scholars like Jeffrey Victor to bring some sanity to the stage.

Second, conspiracy theories—whether satanic cabals, JFK’s assassination, UFOs at Area 51, or US government involvement in 9/11—function both as a means of explanation and a mechanism of personal control. That is, they explain why bad things happen and locate the perpetrators. Doing this allows for some sense of control over one’s environment. In many ways, it’s much easier to believe that there are dark forces at work—a belief that is reinforced, once again, by an entire range of media products—than to accept that bad things happen, sometimes at the behest of bad people, and that we suffer because we are at the wrong place at the wrong time, or because we have contributed to our own suffering. How many people do you know are willing to blame everyone from Satan to Stalin for the things that go wrong in their lives, without ever once looking at how they contribute to their own misfortune? Now, extrapolate that to entire segments of society, and you have the power of the conspiracy theory. Tie that to the universalising force of religion—in the sense of being caught up in a grand chess game between God and the Devil—and you begin to see some of the power of the conspiracy theory and the sociophobic it both relies on and reinforces.

Third, for hundreds of millions of people Satan is very real, hell is very real, and the demonic is a part of their everyday lives. A number of Gallup polls, for example, indicate that in the U.S. belief in the Devil runs over 90% in people who attend church weekly. It’s much lower in Canada and Britain, but the U.S., obviously, is the major market for these films. Indeed, in one poll, 50% of those who either rarely or never attend church say they believe in hell! That’s an incredible figure that implies something very significant about the depth to which these fears are embedded in our society.

TheoFantastique: Another section of this chapter touches on Wiccan and Witchcraft in cinema. I was struck by your discussion of dueling theologies as expressed in the original The Wicker Man and The Craft. What does this duel look like in both films, and how has it changed in the decades between the first film and the second?

Doug Cowan: In The Craft, it’s much more subtle; it’s there, but you have to be much more in tune with different religious traditions to pick up a lot of it. You have to pay attention to see it. The girls begin their group—which they call a circle, never a coven—in the midst of a Catholic high school. When Bonnie, Nancy, and Rochelle are considering Sarah for membership, they’re shown sitting under a mural of the Madonna, who seems to be inclined in prayer towards (for?) them. At daily mass, as the girls giggle and fuss, flush with the powers they believe they’ve tapped, in the background is the priest talking about the tree of knowledge and the disaster its fruits can bring. Oh yes, and there’s the crucifix over the main entry to the school,

with Jesus giving the finger to all who pass beneath. I don’t know whether that was a trick of the light, though I’ve run the shot in zoom and super-slow, and it looks intentional on director Andrew Fleming’s part. He makes no mention of it on the DVD commentary, however, and if you were watching the movie in a theatre, it goes by so quickly you might have said, “Hey, was that Jesus just…?” None of these is conclusive, in and of itself, but cumulatively they point to The Craft drawing on a decades-old tradition in cinema horror of what I call in the book “dueling theologies.”

Subtlety, on the other hand, was never Hammer’s long suit. Films like The Wicker Man, which I point out is really only a horror film on a couple of fronts—the general horror that Sergeant Howie feels when he encounters the people of Summerisle, and the more specific horror in the last six minutes as he is sacrificed in the wicker man—are an extended and often very explicit debate between contending belief systems. When Howie (Edward Woodward) arrives on Summerisle, he is appalled at the rampant paganism he sees around him, and by the open way in which the children are socialised into the religion. As a good churchman—in a dream sequence, we see him reading scripture at his church and receiving communion—he feels as though he has fallen fully down the rabbit hole. This is only confirmed for him when he meets Lord Summerisle (Christopher Lee, who took no payment for the film, and which he still regards as one of his finest roles). Consider this brief bit of dialogue:

SUMMERISLE

It’s most important that each new generation born on Summerisle be made aware that here the old gods aren’t dead.

HOWIE

And what of the true God, to whose glory churches and monasteries have been built on these islands for generations past? Now, sir, what of him?

SUMMERISLE

Well, he’s dead. He can’t complain. He had his chance and, in the modern parlance, he blew it.

Though there are more mundane, and, indeed, insidious explanations offered for the Paganism that has taken root on Summerisle—in a quasi-Marxist manner, Lord Summerisle’s grandfather used the old religion to rouse the islanders from apathy when he took over the island in the mid-eighteenth century—we are left at the end ambivalent about the nature of religion and the power it wields over its followers. The theological conflict remains unresolved, allowing viewers to map onto the story their own experience and expectation of religious belief and practice. When Summerisle tells Howie, for example, “We don’t commit murder up here, Sergeant, we’re a deeply religious people,” he is being entirely truthful. In his mind, and in the minds of the islanders, the Wicker Man sacrifice is not murder; it is, in fact, an honor of sorts for the victim. While Howie dies hoping for the life everlasting his religion has promised him, the Summerisle pagans continue hoping that their propitiatory sacrifice will bring back a bountiful harvest. Both, though, are caught on the point between faith and fear: with his dying breath, Howie entreats his god, “Let me not undergo the real pains of hell because I die unshriven,” while the final shot of the film shows the sun setting in the Atlantic, as the Wicker Man’s head falls, burning, out of the frame. Is Howie right, then, that the bounty will not return because apples were never meant to grow in the Hebrides, and the sun has indeed set on their Pagan beliefs?

These two films present their dueling theologies in very different ways, and I think one of the main differences is what audiences are willing to accept now. Hammer films are nostalgic in their directness, while movies like The Craft strive for a realism that filmmakers hope will not only allow audiences to suspend their disbelief, but will in some sense transcend it.

TheoFantastique: In this section on Witchcraft in film you also touch on the issue of differing interpretations. you state that, “Finally, there is the way in which The Craft has been interpreted by those who have either been influenced by it to explore Paganism, by those who critique it as an inaccurate representation of their religious tradition, or by those who see it as the latest foothold in Satan’s war of spiritual domination.” Of course, we see the same dynamics involved in interpretations of Harry Potter. What accounts for these differing interpretations, and what does this say back to the careful film interpreter about the nature of literature and film as artistic genres, and how these relate to the religions concerns of the various interpreters?

Doug Cowan: The original Wicker Man had a very interesting epigraph at the beginning: before the opening credits roll, the producers thank “the Lord Summerisle and the people of his island . . . for this privileged insight into their religious practices and for their generous co-operation in the making of this film.” It’s entirely fictitious, of course, but it feeds the sociophobic we’ve been talking about, and, as well, it serves to reinforce belief systems people want to consider historically accurate and in which they want to participate. A number of online discussions about the film speculated on the nature of sacrifice, and how the wicker man could be symbolically represented in modern Pagan ritual, for example. They used the film almost as a text for their deliberations—which is what it became, in fact.

I think it’s relatively rare that people are “changed forever” by a film, although we see this kind of claim from time to time. Rather, I think that what people take from a film—any film—is largely a function of what they bring to it. Of course, this is hardly a new insight, but it bears repeating in the context of sociophobics and what I have called elsewhere “sociospera”—the culturally constructed hopes of different groups. Those who identify themselves as Pagans or who want to identify themselves as such are going to see in a film like The Craft something very different than conservative Christians who, like Bill Schoebelen, regard Wicca as “Satan’s little white lie.” A film like this—indeed most horror films, I would imagine—are not going to change anyone’s mind about anything. What they will do is exploit and reinforce those beliefs, fears, and hopes that audience members bring with them to the theatre.

In terms of “the careful film interpreter,” I’m not really sure what to say. If someone takes a piece of art—a novel or a poem, say—and builds a belief system around it, attracts followers, uses the mythology either implicit or explicit within the novel or the film to touch some part of the human spirit, are they any less careful in their interpretation than someone who correctly points out that witches were not burned in New England (they were hanged) despite what a movie like Horror Hotel shows? On the other hand, we have examples where artistic products have generated real life movements. Robert Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land, for example, was the impetus for what became the Church of All Worlds, the first legally incorporated modern Pagan group in the U.S. In the 2001 British census, on the other hand, somewhere around 400,000 Britons wrote in under “Religious Preference” that they were “Jedi Knights.” Now, an author or director can say all they want, “Hey, that’s not what I meant, you’ve got it all wrong!” But that’s not going to stop people from interpreting things according to their predispositio

ns, and taking from them what they find useful—whether a bouquet or a brickbat.

TheoFantastique: In our exchanges you have raised the question of authority as it relates to interpretation in this and other areas. How might Christian and Pagan views of authority be more alike than both systems might like to acknowledge, and how might this lend itself to similar concerns being expressed by how Witchcraft is allegedly being portrayed in literature or film?

Doug Cowan: This is an important, and very complex, issue. Obviously, both modern Pagans and Christians have a vested interest in differentiating themselves, one from the other. Many people have left Christianity for modern Paganism, and are vitriolic in their renunciation of their former religion and their insistence that their current path is entirely different. Of course, the reverse is also true. And, people have a need to be right, or at least feel that they are right in what they believe, and they will go to all kinds of lengths to reinforce that belief. Which is entirely reasonable, since it makes no sense for people to believe things they know are wrong or untrue. However, simply believing something, or pointing out where another’s belief system is problematic, is no guarantee that one’s own system is either consistent, logical, or in accord with reality in any way.

That said, one of the places I see a convergence is at the level of authority and orthodoxy, in the case of modern Paganism incipiently so. Put bluntly, in terms of their claims to religious authority, and especially who is an authentic member of the group, the Pagans I read online in any number of discussion forums sound amazingly like fundamentalist Christians I follow on a couple of different countercult lists. The difference is that one group is very explicit about the fact and the terms of its orthodoxy, the other isn’t. However much modern Pagans do not want to admit it, there is a will to orthodoxy running right through the tradition—or family of traditions. Consider, for example, modern Pagans whose belief system is predicated on an affective and authoritative personal gnosticism—if it feels right to you, then it must be right. Modern Pagan literature is replete with this kind of claim. Then look at the reaction of modern Pagans when someone wants to claim explicitly Christian figures—Jesus, Mary, St. Francis, or even Satan—as part of their personal Pagan pantheon. The reaction is, shall we say, energetic. That is, you can include any god or goddess you want in your pantheon, as long as it has nothing to do with Christianity. I’ve seen modern Pagans blithely contend that Kwan Yin is a Wiccan deity, yet refuse to acknowledge Mary in the same way. What this demonstrates, of course, is that there is an orthodoxy; it is just hidden and operates differently from the kind of orthodoxy that says “ours is the only way to access the Divine.”

In terms of films, on the other hand, this is important because they participate in the cultural representation of, say, modern Witchcraft. In a number of recent films, The Craft among them, but more obviously in TV series like Charmed, the cultural construct of the Witch has changed. She is now a young, beautiful woman with extraordinary powers. Rather than a wicked temptress, in terms of Charmed, for example, she is a magically powered superhero. This is important for two reasons. First, entertainment products provide us with images for emulation—think of the fashion craze ignited by Miami Vice two decades ago, the young girls trying (God knows why) to emulate Paris Hilton, carrying little imitation Gucci bags and stuffed dogs and oversized sunglasses, or, in our case here, the thousands of young men and women who see in products like Charmed and The Craft something to emulate—perhaps not entirely, but in part.

Second, this emulation draws on and reinforces cultural standards (read: impossible ideals) of beauty. As I say in the chapter, it is hardly unimportant that the main characters in many of these products are exceptionally attractive young women, just like the four Charmed ones (three of whom have been named to different magazines’ “100 Sexiest Women in the World” lists, while the fourth has posed several times in Playboy). Try to imagine either production succeeding with a storyline about three young Druids played by Pauly Shore, Jack Black, and Pee Wee Herman. An unfair comparison, perhaps, but not unrealistic given Hollywood’s obsession with an ideal of physical (and by implication sexual) perfection, and the effect that obsession has had on hundreds of millions of young men and women around the globe. Online Pagan discussion forums, for example, reveal a wide range of opinions about The Craft. Some participants love the film and see it as an accurate, though essentially admonitory portrayal of their religious beliefs and ritual practice. Others despise it, wanting to concentrate only on the salutary aspects of their faith and noting the positive influence of Lirio (the owner of the Pagan bookstore, and the wisdom figure in the film). One Yahoo! discussion group even includes a “Cool Entertainment or Bad Idea” item in its new member questionnaire, and lists both The Craft and Charmed. Participant profiles in that particular discussion community are shaped, however modestly, by their reaction to these particular media products. For many members, it is indeed “cool entertainment,” though almost all point out what they consider its flaws. Once again, they focus only on the positive aspects of their faith, falling prey, as do so many other religious believers, to the “good, moral, and decent” fallacy that marks modern Paganism no less than any other tradition.

TheoFantastique: In the final section of the chapter you touch on the area of sexual power and women, and you note how this has particularly been portrayed in vampire films. How has fear of sexual power and women played into various historical depictions of Witchcraft, and how have these influenced various cinematic treatments?

Doug Cowan: This is one of the sections of the book I really wish could be longer, since it is a vastly underexplored area. Perhaps there’s another book there… Anyway, as I say in that last section:

Fear of witches and the sexual power of women go back many hundreds, if not thousands of years. By the Middle Ages, this fear had become so deeply embedded in Christian systematic theology that works such as Malleus Maleficarum and Compendium Maleficarum today read like pure studies in sexual repression and projection. Reinforced by journalistic “exposés” such as Sex and the Occult, Sex and the Supernatural, and Sex in Witchcraft, twentieth-century cinema horror has followed diligently in this wake. The advertising poster for Hammer’s The Witches, for example, which relies on an unsteady amalgam of witchcraft, voodoo, and indeterminate occultism, reads ominously (but invitingly):

What does it have to do with sex?…

Why does it attract women?…

What does it do to the unsuspecting?…

Why won’t they talk about it?…

What do the witches do after dark?

The message, of course, is “Come see the movie and we’ll show you!” Tigon British Films, one of Hammer’s competitors in the late 1960s and early 1970s, produced a couple of similar attempts: The Curse of the Crimson Altar, starring Barbara Steele as the deathless witch, Lavinia Morley, and Virgin Witch, an otherwise forgettable lesbian romp whose star, Vicki Michelle, is best known for her portrayal of Yvette Carte-Blanche in the long-running British comedy, ‘Allo ‘Allo. Mario Mercier’s ultra-low budget Erotic Witchcraft leaves nothing to the imagination, while on this side of the Atlantic, many films

based on the premise of erotic witchcraft quickly devolved into little more than supernatural vehicles for softcore pornography. The cinematic association of witchcraft and overt sexuality even extends to light comedies such as Bell, Book and Candle. When Gillian (Kim Novak) is still a witch, her dress is bohemian and alluring. When she falls in love with Shep Henderson (Jimmy Stewart) and loses her powers—when she is no longer a witch—her costume also changes, from slinky pullovers, bare backs, and bare feet to a conservative, high-necked dress, and satin pumps.

Sex and fear couple in virtually all aspects of cinema horror, from vampire movies to witchcraft films, from Universal monster features like Creature from the Black Lagoon and The Mummy to Italian giallo cannibal films and more recent American slasher/torture efforts. Whether hetero- or homosexual, most focus on the woman’s body as the object of fascination and desire, the site of repression and aggression, and, often, the locus of evil and catastrophe. Indeed, in many of these films, especially the nunsploitation films I also discuss, it is as though Augustine and Tertullian—two principal architects of Christian misogyny—sat in on the script sessions, costume meetings, and principal photography.

TheoFantastique: Doug, thanks again for allowing me to ask some questions that tease out elements discussed in your book. I look forward to its release and to promoting it on this blog.

re: Wicker Man, one of the many stories about the film (I can’t remember the source offhand) involves that tension of the Pagan/Christian point of view. That the director felt Howie was a victim and found him more sympathetic, whereas the writer found Howie to be the aggressor. And the writer and director worked together on the production, so this tension came out in the film. And as a side note, I was first shown the film by my original magical teacher as a manifestation of the God (very Frazerian and all that).

I also have a comment about Doug’s comment on orthodoxy. Just because some Pagans might get very upset about including Jesus and Mary in a Pagan pantheon, does that mean they are defending an orthodoxy? The notion that Doug mentions of an “affective and authoritative personal gnosticism” is absolutely not contradictory to his subsequent comments about some Pagans being upset about including Christian ‘deities.’ The fact is, some Pagans do accept Christian deities and some don’t. Perhaps those that don’t and are extremely vocal about it are presenting their own orthodoxy, but it in no way is representative of some overarching Pagan orthodoxy.

In fact, look at the popularity of the novel, Mists of Avalon, where the cult of the Virgin Mary is presented as a version of Goddess worship. I’d venture to say that there are probably a great deal of Pagans who interpret Mary that way. I think it’s always a mistake to assume that the loudest online voices are always representative of the community as a whole.

I agree with buffyologist on the “loudest aren’t always the most representative”. You can’t judge the entire pagan community (or any group, for that matter) based on the internet. Online interaction has the tendency to bring out the worst in people–flame wars, saying things that they’d *never* say to someone’s face, etc.

Now, I would assume, not having read any of Cowan’s works (though I’m not tempted to, thanks to this intriguing interview), that he has encountered pagans in person. I’d just remind him that, overall, we are a collection of individuals following a wide variety of spiritual paths, and there’s really nothing you can say about us other than that we self-identify as “pagan” (among other, more specific terms).

Overall, though, excellent interview. I enjoyed the read, and I think there were some good points raised. The media in general like to play on people’s fears–that sells. The adrenaline, mixed with justification for one’s most irrational terrors, are the perfect pablum for this culture. Less thinking, more fearing–*regardless* of religion.

I’m also very glad Cowan brought up the sociological use of the word “cult”. That’s by far one of the most misunderstood words out there, semantically speaking. I remember sitting in sociology class, learning about the differences between a cult, a sect, and a religion, and thinking “Wow, it would be a lot easier to talk about being pagan if these words were more commonly used in this fashion”.

Finally, regarding minority religions (and various fringe subcultures) in the media in general, a good friend of mine wrote up an excellent blog post about it a couple of years ago: http://heron61.livejournal.com/191533.html . In it he delineates four stages of increasing acceptance as demonstrated by media portrayals of a group in question. I think it fits in nicely with the discussion of neopagan religions and other groups, and it shows the historical pattern that the media has had towards the fringe-moving-inward in general.

Good interview, overall.

Wendy Griffin, ‘The Embodied Goddess: Feminist Witchcraft and Female Divinity’, Sociology of Religion, 56.1, Spring 1995, is one academic source where in the field work participants of a ritual state (and embody) Mary as an aspect of the Goddess. Just a FYI.