Some recent research for new sources of material led me to the volume Roman Catholicism in Fantastic Film: Essays on Belief, Spectacle, Ritual and Imagery (McFarland, 2011), edited by Regina Hansen. Hansen is is a senior lecturer at Boston University College of General Studies. This volume provides a helpful consideration of the important influences and contributions of Roman Catholicism to horror, fantasy, science fiction and other expressions of the fantastic. Following is our discussion of this book.

Some recent research for new sources of material led me to the volume Roman Catholicism in Fantastic Film: Essays on Belief, Spectacle, Ritual and Imagery (McFarland, 2011), edited by Regina Hansen. Hansen is is a senior lecturer at Boston University College of General Studies. This volume provides a helpful consideration of the important influences and contributions of Roman Catholicism to horror, fantasy, science fiction and other expressions of the fantastic. Following is our discussion of this book.

TheoFantastique: Regina, thank you for your time to discuss a great book. I’m not aware of previous treatments of this topic in book form which, if true, is curious given the prevalence of Roman Catholicism in horror and other genres of the fantastic. How did you come to develop this subject matter and these contributors?

Regina Hansen: I started planning for the book during discussions with friends at the International Conference for the Fantastic in the Arts (two of the book’s contributors, Christa Jones and Isabella van Elferen were part of those discussions). You’re right in that there hasn’t been much scholarly inquiry into this particular topic. There have been some terrific books on Catholicism in film, and Victoria Nelson’s essay on “faux Catholicism” in works like The Da Vinci Code was very helpful in our thinking about this book. The great thing is that many of the volume’s contributors wanted to be part of the project precisely because they’d always wanted to write on the topic of Catholicism in fantastic film but never had a chance. I came to the idea from both personal and scholarly interests. My family (at least my mother’s side) were very much steeped in the supernatural aspects of Catholicism: my great-grandmother really understood and studied the various devotions, to Mary especially. My grandfather read Aquinas and Francis of Assisi for fun. Being a part of that tradition really opened me up to the fantastic, to supernatural and metaphysical themes – in the stuff I like to write about, and in what I like to read and see in film. I think you’d find that to be true of many people actually. Still, in putting together the book, I didn’t need or want everyone to have the same point of view as I do. I love being a Catholic; I love everything about the practice of my faith – even though there’s also a lot that disappoints me on the social level. There’s plenty to question and a lot of that questioning has been done by filmmakers and critics in the fantastic. I wanted to have contributors who represented a spectrum of attitudes toward Catholicism and a spectrum of scholarly approaches as well. I think we really succeeded in that goal.

TheoFantastique: Can you comment on the various ways in which Roman Catholicism is uniquely suited to provide material for the fantastic in contrast with Protestantism?

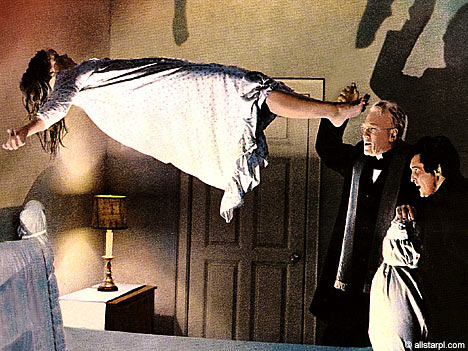

Regina Hansen: The elements of Catholicism that make their way into films of the fantastic tend to be the ones that were rejected during the Reformation as idolatrous or pagan – devotion to Mary and the saints, the use of statues or other physical objects as a means of veneration or an aid to worship. But, I wouldn’t say it’s just a Catholic/Protestant thing. I think filmmakers are drawn to the non-Enlightenment, irrational aspects of Catholicism, in the same way that Gothic novelists used to be. Catholics are supposed to fully believe in a supernatural world, in supernatural events occurring on a daily basis – the priest actually turning bread and wine into Christ’s body and blood, Mary and the saints as intercessors with God, angels, demons, all that stuff. Many Protestants are meant to believe in some of those things, too. The recent movie Exorcism deals with demons, etc. from a Pentecostal rather than Catholic perspective. Still, Catholicism has been around longer, and there is a Catholic presence in almost every country in the world. Catholic practice and iconography are weird and familiar at the same time, especially in the United States, where there weren’t really a lot of Catholics until the 1800’s.

Regina Hansen: The elements of Catholicism that make their way into films of the fantastic tend to be the ones that were rejected during the Reformation as idolatrous or pagan – devotion to Mary and the saints, the use of statues or other physical objects as a means of veneration or an aid to worship. But, I wouldn’t say it’s just a Catholic/Protestant thing. I think filmmakers are drawn to the non-Enlightenment, irrational aspects of Catholicism, in the same way that Gothic novelists used to be. Catholics are supposed to fully believe in a supernatural world, in supernatural events occurring on a daily basis – the priest actually turning bread and wine into Christ’s body and blood, Mary and the saints as intercessors with God, angels, demons, all that stuff. Many Protestants are meant to believe in some of those things, too. The recent movie Exorcism deals with demons, etc. from a Pentecostal rather than Catholic perspective. Still, Catholicism has been around longer, and there is a Catholic presence in almost every country in the world. Catholic practice and iconography are weird and familiar at the same time, especially in the United States, where there weren’t really a lot of Catholics until the 1800’s.

TheoFantastique: Readers might first think of vampires and demonic possession in connection with Roman Catholicism, but while your book touches on these areas it also sketches broader areas of influence. Can you touch on the connection of this branch of Christendom to the broader realm of the monstrous and fantastic?

Regina Hansen: There are a lot of issues. For instance, in fantasy film and literature, so much of the traditional narratives grow out of Medieval romance, or have a Medievalist aesthetic that goes back to the pre-Raphaelites and the work of Morris and Rossetti. That kind of aesthetic is just not possible without dealing with the iconography of Catholicism, even if you end up changing it around a bit. Also, people don’t necessarily think about religious movies as movies about the fantastic, but of course they are. Traditional stories of saints’ lives are as full of that kind of stuff as anything from J.K. Rowling. In our book, Paulo Cunha and Daniel Ribas write about Marian apparitions in film – particularly Our Lady of Fatima. These are films about a supernatural personage appearing to a group of children and performing supernatural feats, like making the sun spin etc. That’s the fantastic right there. Also, one reason I wanted to do this book was to show how often entirely realist films create an atmosphere of the fantastic or uncanny simply by adding elements of Catholic religious practice or belief to the narrative. Kathleen Urda and Brett Gaul talk about this in their chapters, on the new Brideshead Revisited film and Gone Baby Gone respectively. A really great example (not in the book) is in The Godfather when Michael Corleone’s enemies are being slaughtered as he takes part in a baptism, and is supposedly rejecting Satan.

TheoFantastique: One of the chapters I connected with was the one by Christopher McKittrick in his analysis of the films of Terry Gilliam. I was surprised to learn of his being raised Protestant, and yet he has incorporated Roman Catholic elements in his films of the fantastic. How has this religious tradition impacted his work?

Regina Hansen: Again I see the impact in the Medievalist aesthetic of a lot of his work, from the interstitial cartoons he did for Monty Python’s Flying Circus to Monty Python and the Holy Grail to The Fisher King. At the same time, Gilliam/the Pythons pretty cleverly satirize some Catholic beliefs or doctrine, as in the song “Every Sperm is Sacred,” from The Meaning of Life. Chris McKittrick writes about all this but also suggests that the narrative arc of many of Gilliam’s films echoes theological questions that have often brought Catholicism and Protestantism into conflict: free will and the problem of evil, the importance of good works relative to faith. These are interesting things to think about.

TheoFantastique: I enjoyed Em McAvan’s exploration of The Lord of the Rings. How has Tolkien’s text come to involve multiple readings and layers in terms of Tolkien’s Roman Catholicism as well as New Age and pagan elements?

TheoFantastique: I enjoyed Em McAvan’s exploration of The Lord of the Rings. How has Tolkien’s text come to involve multiple readings and layers in terms of Tolkien’s Roman Catholicism as well as New Age and pagan elements?

Regina Hansen: Tolkien was an observant Catholic; most people know that. At the same time, we don’t usually see LOTR as having much Catholicism in it. It seems much more based in Anglo-Saxon or Norse mythology, the kind of literature Tolkien studied and taught. Em sees the influence of Tolkien’ Catholicism in the novel’s sacramentality, its use of holy objects. She suggests that objects like “Galadriel’s phial of light and the elvish lembas bread” represent “the sacred embodied in the material.” (43) This idea is certainly central to Catholic practice, though not unique to it. Em also suggests that the films replace that element of sacramentality — of particular objects carrying particular holiness — with a more generalized New Age “reverence for all living things.” (49) So, if you look at the novel and films together, there really is the interplay among paganism, Catholicism and New Age thinking, and also, as Em reminds us, the danger of consumerism – taking objects so seriously, making them so holy that they become more important than what they represent, or just things to be acquired.

TheoFantastique: I’m finalizing some research for a chapter in the forthcoming book The Undead and Theology, so Jana Toppe’s chapter on zombie films and the Resurrection and Eucharist were of special interest. In what ways might zombie “resurrection” and the consumption of flesh and blood be read as a satire of Resurrection and Eucharist?

Regina Hansen: Christianity and Catholicism in particular make certain promises – people will achieve eternal life through the consumption of Christ’s body and blood; there will be bodily resurrection at the end of time. Zombie films sort of half fulfill these promises: Zombies eat flesh. Zombies live forever (or almost, until they get shot in the head) but they live forever without identity, without soul. Zombies are walking resurrected bodies, but just bodies and corrupt ones at that. The Zombie Apocalypse involves the resurrection of the body but, as Jana says, leaves out the promise for a better world. Interestingly, as Jana points out, early zombie films (like The White Zombie) were based on Haitian Voudoun, or a heavily exoticized version of it anyway. Since Voudoun has many Catholic elements, it seems as if Catholicism and movie zombies have been interacting since the early days of film.

TheoFantastique: I was pleased to see a discussion of The Others, a ghost story that was very well done. How does Roman Catholicism inform the identity and struggle of the main character, Grace, portrayed by Nicole Kidman?

Regina Hansen: Grace is obsessed with the “rules” of Catholicism, and her interpretation of them. She follows those rules obsessively, as a way to hide from herself the truth of her present situation (spoiler alert) that she’s dead and also killed her children, that she is the “other,” the ghost in the house. In their chapter, Anabel Altemir Giral and Ismael Ibanez Rosales suggest that in clinging to rules, to dogma, Grace not only blinds herself to her own state of being but to the potential for holiness all around her. They write about Grace’s denial of her “sacramental imagination,” her inability to see the objects and people in the house as potential “revelations of God’s grace.” (277) A full understanding of Catholicism includes the experience of a world alive with spirit and holiness. As happens with the character of Grace, blind adherence to rules for their own sake can cut one off from that world, that sacramental experience.

Regina Hansen: Grace is obsessed with the “rules” of Catholicism, and her interpretation of them. She follows those rules obsessively, as a way to hide from herself the truth of her present situation (spoiler alert) that she’s dead and also killed her children, that she is the “other,” the ghost in the house. In their chapter, Anabel Altemir Giral and Ismael Ibanez Rosales suggest that in clinging to rules, to dogma, Grace not only blinds herself to her own state of being but to the potential for holiness all around her. They write about Grace’s denial of her “sacramental imagination,” her inability to see the objects and people in the house as potential “revelations of God’s grace.” (277) A full understanding of Catholicism includes the experience of a world alive with spirit and holiness. As happens with the character of Grace, blind adherence to rules for their own sake can cut one off from that world, that sacramental experience.

TheoFantastique: I would love to have seen someone grapple with the place of Roman Catholicism in the films of Guillermo del Toro. Are there any plans for a follow up volume that might include explorations like this?

Regina Hansen: Del Toro’s work is fascinating in this regard. He very much rejects organized religion and some of his nastiest characters are Catholic clerics. At the same time, he often portrays people of simple faith, who happen to be Catholics, in a very appealing way, and his work seems to find some kind of real power/value in Catholic objects and images. I’m working on a single author volume right now that will continue some of the work started in Roman Catholicism in Fantastic Film, and I do plan to include Del Toro.

TheoFantastique: Regina, thank you again for a great book, and for your time in discussing aspects of this volume.

Regina Hansen: Thank you very much, John.

Great interview. Looking forward to reading more of Professors Hansens work.