One of the great things about having a niche blog like this one is finding fellow academics exploring the horrific and fantastic. This was the case with Andrea Subissati who wrote her MA thesis When There’s No More Room in Hell on the sociology of zombies, since published as a book through Lambert Academic Publishing. Thankfully I was able to track Andrea down, and she made some time in her schedule to discuss her thesis, and further thoughts on zombies and popular culture.

One of the great things about having a niche blog like this one is finding fellow academics exploring the horrific and fantastic. This was the case with Andrea Subissati who wrote her MA thesis When There’s No More Room in Hell on the sociology of zombies, since published as a book through Lambert Academic Publishing. Thankfully I was able to track Andrea down, and she made some time in her schedule to discuss her thesis, and further thoughts on zombies and popular culture.

TheoFantastique: Andrea, thank you for your willingness to discuss your book and helping us understand some of the meaning of zombies in our culture in greater depth. Your book came out of your MA in Sociology at Carleton University. How did you develop a research interest in this topic, and how did you persuade the university to allow you to focus on this for a thesis project?

Andrea Subissati: Thanks, John. When I started my MA, I intended to write my thesis on the recent resurgence of traditionally “domestic” pastimes among young women; knitting in particular. Throughout the course work portion of my studies, I came across Wes Craven’s The Serpent and the Rainbow, which led me to Wade Davis’ ethnographies on zombies in Haitian Vodoun communities. I became intrigued by the transformation of the traditional mythological zombie to their horror movie counterparts, and this transformation or “Americanization” became the foundation for my thesis.

I was further compelled to write on this topic because at the time I started writing (2007), it was apparent that zombies were more popular than ever and were spreading to other forms of media, including television, video games and classic literature. And yet, in spite of their popularity, there were surprisingly few academic resources that gave zombies as much analytical weight as other horror movie monsters, like vampires or mummies. All these factors made a compelling argument for an academic thesis on the cultural study of zombies, and my supervisor was actually eager to oversee such a relevant and as of yet untapped topic in sociology.

TheoFantastique: What analytical strands do you bring together in your analysis of the zombie, particularly Romero’s defining work on this cultural icon?

Andrea Subissati: Cultural materialism is a method for analyzing literature within a Marxist framework, one that focuses on conflict and power imbalances portrayed in text. I use this viewpoint to argue for the critical merit of these films as radical texts that have potential to inspire critical thought about real social issues including consumerism, racism and mistrust in military authority (to name a few). I also draw from tenets of active audience theory to focus my analysis on the analytical potential of the fans and to keep this as distinct from the intentions or motivations of the filmmaker.

TheoFantastique: Many commentators and critics have noted Romero’s critique of consumerism in his zombie films, particularly Dawn of the Dead. In your analysis do you see a variety of critiques in this regard, and what else can we understand Romero to be offering by way of cultural critique through his very different approaches to his canon of zombie films?

Andrea Subissati: Of what little academic resources I was able to find on zombies, the elements of consumerism in Dawn of the Dead were the most popular. The analogy of zombies to shoppers is rather overt, but there are plenty of other critical topics tackled in that movie, particularly in Peter’s theological remarks about his Vodoun granddaddy about “When there’s no more room in hell”. I found that observation to be particularly profound which is why I chose the quote as the title of my book.

Andrea Subissati: Of what little academic resources I was able to find on zombies, the elements of consumerism in Dawn of the Dead were the most popular. The analogy of zombies to shoppers is rather overt, but there are plenty of other critical topics tackled in that movie, particularly in Peter’s theological remarks about his Vodoun granddaddy about “When there’s no more room in hell”. I found that observation to be particularly profound which is why I chose the quote as the title of my book.

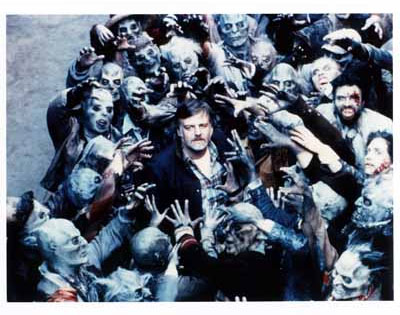

I believe that all of Romero’s films featuring zombies are uniquely poised to inspire critical thought because instead of focusing on the undead rising, they focus on the people dealing with the undead rising, and the cultural trappings that keep them from being able to cooperate and survive the onslaught. More and more zombie movies today are focusing their gaze to the zombies themselves and all of the effort goes into making them faster, scarier, grosser, etc. For me, the best thing about Romero’s treatment of zombies is how he is able to show the monstrosity that human beings are capable of, which is a whole lot scarier than a brain-eating corpse!

TheoFantastique: I have been interested in the academic study of the Zombie Walk phenomenon, from sociological, anthropological, and perhaps even religious studies perspectives. I was pleased to see you mention this phenomenon twice in your book. Do you have any thoughts on the meaning of this experience for participants and what they may be saying about issues related to both personal identity and their feelings about society?

Andrea Subissati: The zombie walk is such a fascinating combination of fan convention, flash mob and guerrilla theater. I love it precisely because it’s so difficult to explain. Certainly, there is good clean fun to be had. As a fan of the genre, it is pretty enjoyable to see familiar streets and local landmarks overrun with the living dead, but beyond that I feel that the walks are an expression of the special connection that people feel to zombies. So much of modern life treats human beings like a mindless cannibal horde: junk culture, fast food, and overpopulation come to mind as examples. It is almost as though the zombie walks are a cathartic parody of urban life, expressed in a manner that is simultaneously radical and playful.

TheoFantastique: If we could, let’s move beyond your analysis of Romero’s zombies to these creatures in another context. As you know, The Walking Dead television series was very popular for the AMC network last year, surpassing their expectations for the number of viewers. This seems to indicate that the zombie is a figure of interest beyond the confines of the horror and zombie subcultures to a more general audience. With the challenges we face in society at the present time, perhaps similar or worse to that of the late 1970s when Romero produced Dawn of the Dead a decade after the counterculture, why do you think the zombie in The Walking Dead has resonated with so many people?

Andrea Subissati: I think it’s important to note that The Walking Dead TV show was destined to succeed from the start. The graphic novel series has been celebrated since its first issues in 2004, and following the critical acclaim of Mad Men and Breaking Bad, AMC had been established as a juggernaut on the syndicated TV scene. The TV show debuted in 120 countries and deployed a tremendously expensive and far-reaching marketing campaign prior to its release. This story of production and distribution is such a far cry from Romero’s struggles with Night of the Living Dead which was released independently and grew to notoriety and critical acclaim underground.

In my opinion, something important and subversive was lost in The Walking Dead’s journey from graphic novel series to network TV. I think part of the reason The Walking Dead is enjoying more mainstream popularity than the B-movie celluloid of yesteryear is has to do with the subject matter being polished, paraphrased and made more palatable for a TV audience. To put it more simply (and less snobbishly, I hope), I fear that the novelty and violence of the show is what is resonating with audiences rather than the subversive themes that made Romero’s series what it is. I really enjoy the graphic novel series so I am hopeful that the great characters and plotlines will shine in season 2, but backstage tensions and Frank Darabont’s sudden departure are worrisome.

TheoFantastique: In your bio on the back cover of your book I was struck by the fact that you are smart enough to look beyond the academy “in favor of regular paychecks.” One of the ways you do this is through your Undead Clothing company. Can you talk a little about how this came about, what it involves, and how readers can purchase some of your work in this area?

Andrea Subissati: Undeadclothingco is like the evil twin sister to my master’s thesis: they were both born out of the stress, strain and sweat that came from undergoing graduate studies. I knitted on the bus, I crocheted on my breaks and I sewed while I listened to Romero’s commentary of Dawn of the Dead for the hundredth time. The result of all this creativity was a household that had more crocheted slippers than it did feet to fill them, so I started selling my handiwork online and at craft sales in Ottawa.

Andrea Subissati: Undeadclothingco is like the evil twin sister to my master’s thesis: they were both born out of the stress, strain and sweat that came from undergoing graduate studies. I knitted on the bus, I crocheted on my breaks and I sewed while I listened to Romero’s commentary of Dawn of the Dead for the hundredth time. The result of all this creativity was a household that had more crocheted slippers than it did feet to fill them, so I started selling my handiwork online and at craft sales in Ottawa.

Sadly, abandoning academia also meant getting a 9-5 job in an office, where idle hands are looked upon less favorably. Nowadays, my precious spare time is consumed with writing (including work on a chapter for your forthcoming anthology [The Undead and Theology]), roller derby (keeping me off the mean streets of Toronto) and the occasional guest stint on the Rue Morgue podcast (available on iTunes and streaming off the Rue Morgue website). On the odd chance that free time and inspiration strike at the same time, you can find my handmade goodies listed at undeadclothing.ca and on my etsy site (http://www.etsy.com/shop/undeadclothingco?ref=pr_shop).

TheoFantastique: Andrea, thanks again for your time. I enjoyed your book, and am looking forward to your contribution to the anthology. Keep up the great work among the undead.

One Response to “Andrea Subissati: When There’s No More Room in Hell”