Quite some time ago I promoted a forthcoming interview with Stephen Asma regarding his book On Monsters: An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears (Oxford University Press, 2009). As I worked my way through my growing collection of books for research, review, and interviews, On Monsters finally crawled to the top, and I am pleased to share my recent discussion with Dr. Asma. Stephen T. Asma is Professor of Philosophy at Columbia College Chicago, where he holds the title of Distinguished Scholar.

In the interview that follows Asma discusses the thesis of his book as informed by the natural sciences, philosophy and religion.

TheoFantastique: As a philosopher and academic, how did you come to an interest in and exploration of the monster in history?

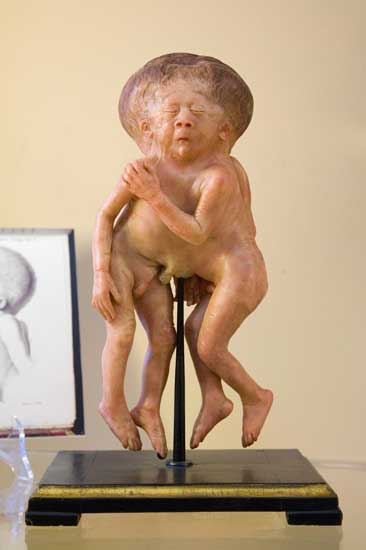

Stephen T. Asma: I’ve always been a fan of old natural history collections and museums, and wrote a book about them in 2001 called Stuffed Animals and Pickled Heads. A lot of these collections contain macabre wet preparations of teratology specimens (severe birth defects, conjoined twins, and so on). So originally my idea was to write about the history of teratology, but then I started to think about the monster as a larger category (folklore, art, and so on). And I wondered what the connection was between all these things called “monster.” That’s how it started.

Stephen T. Asma: I’ve always been a fan of old natural history collections and museums, and wrote a book about them in 2001 called Stuffed Animals and Pickled Heads. A lot of these collections contain macabre wet preparations of teratology specimens (severe birth defects, conjoined twins, and so on). So originally my idea was to write about the history of teratology, but then I started to think about the monster as a larger category (folklore, art, and so on). And I wondered what the connection was between all these things called “monster.” That’s how it started.

When I was getting my PhD, one of my areas of specialization was philosophy of biology. I was interested in Aristotle’s teleological notion of nature and Darwin’s rejection of purpose in nature. The monster is a concept that brings us to the heart of organic form and deviance.

TheoFantastique: In light of Darwinian evolution, how do you see monsters developing in the human imagination?

Stephen T. Asma: After Darwin, Nature is no longer the rational system of Aristotelian Final Causes. God is not in his heaven orchestrating the natural kingdom. Even Isaac Newton’s mechanical watchmaker God is undone by Darwin’s brutal survival of the fittest. This changes the conceptualization of monsters. Monsters after Darwin are just other species (e.g., aliens, or cryptids, etc.) who are also just trying to survive. They bear you no ill-will, and they’re not “evil.” They just need your body to gestate their larval offspring. It’s nothing personal.

TheoFantastique: In your Introduction you describe the monster not only as an archetype, but also as as a cultural category. Can you describe what you mean by this?

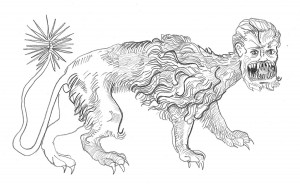

Stephen T. Asma: Well, “archetype” is a loaded term because Carl Jung gave it a psychoanalytical meaning. But the term is older than Plato and I mean it in this more general sense. I think there are a few perennial archetypes or patterns that repeat themselves in monster fears. There are “slithering” creatures, “giants,” “hybrid” chimeras, “swimmers”, “crawlers” of the arachnid type, maybe big “carnivore predators” and so on. These prototype monsters have some basis in real biology, but they obviously become heavily embellished. As a cultural category, each of these (and more) can be further articulated and nuanced through folklore, literature, pictorial traditions, and so on.

TheoFantastique: Also in the Introduction, you state that “imagination is more active in our picture of reality than we previously acknowledged.” How significant is the monster to our imaginative conception of the world around us?

Stephen T. Asma: We don’t just record the external world like a camera, nor do we mirror it. Instead, we shape our experience of nature through the expectations of our values and desires, and our imaginations intermingle with perceptions to create an already mediated reality. Psychologists have demonstrated, for example, that when a person is afraid, they will radically exaggerate the size of the perceived threatening person –adding a full foot to the size of an intruder. I think our human vulnerabilities are always swimming around in our imagination, and as we make our way through a dark street we hasten our step or whistle to mask our fear. All the while, we can’t help but imagine some worst-case scenario, involving serial killers, or sewer mutants or whatever. Our brains seem hard-wired to err on the side of caution, so all of us have phobia potential. In moderation, some imagination-based fear is a good survival trait.

TheoFantastique: Your book is divided into four parts with an analysis of ancient monsters, medieval monsters (of the religious type), scientific monsters, and inner (psychological) monsters. Which of these categories, and the monsters within them, are the most frightening for you and why?

Stephen T. Asma: I’m most phobic about deep or murky water. Like any average urbanite, I don’t have to fear predators from the forest, but there are still many places where one can be killed by animals. I just spent a few weeks in East Africa, and there are many ways you can die there if you’re not careful (e.g., big cats, crocs, buffalo, etc..). Like many others, I’ve also hiked in Grizzly bear country and felt great fear. But as a Chicagoan, I go around without much worry about natural predators. Still, Chicago has its share of human predators, as every big city. This might explain why monster narratives these days stress the serial killers, or criminal pathology monsters. Most people are living in dense cities and their fears are less about nature and more about other people.

TheoFantastique: You make an interesting comment at the conclusion of chapter 12 when you state, “That older paradigm held out the inevitability of monstrous defeat by divine justice, but the contemporary monster is often a reminder of theological abandonment and the accompanying angst.” It would seem that monsters can serve both the religious and secular imaginations. Would you agree?

Stephen T. Asma: Yes, I would agree. I try to show that monsters and fear of monsters cross many paradigm shifts –from Pagan to Christian, to biological, to psychological, and so on. Theological monsterology usually sees monsters as part of a larger morality tale. For example, giants are laid low because of their arrogant pride, and spawn of Cain –like Grendel –meet their deserved destruction in time. Whereas secular monster narratives are more disturbing because they lack the righteous restoration of justice and good that one finds in most theological narratives.

TheoFantastique: One final question if I may. In the end notes for chapter 12 you state: “Undead monsters are particularly uncanny, I would argue, because they embody our narcissistic commitment to extended life, but also our mature commitment (via the reality principle) that no such possibility exists.” This is similar to my thoughts on an aspect of the popularity of the zombie. In a postmodern and post-Christendom West I wonder whether the zombie may be understood in part as a form of resurrection, but in reaction against the perceived loss of credibility in the Christian metanarrative, resulting in a bodily “survival” of death that represents a more nihilistic apocalyptic. Your thoughts?

Stephen T. Asma: This is an interesting interpretation. The old metanarrative of resurrection is untenable in our skeptical and ironic age, but the deep drive for immortality can’t be squelched. Zombies also have unique qualities that trigger the dynamic of love/hate, attraction/repulsion. The zombie, like the vampire, is a kind of immortal: chop his leg off, he’s still coming; blow a hole in his chest, he’s still coming. His life span is indefinite and he’s indestructible. So the little narcissist inside us really likes the immortal aspect of the zombie and the vampire. We unconsciously crave that kind of staying power and durability, but our narcissistic desire to cheat death is impossible to sustain in the face of mature experience. Reality regularly reminds us, as we are growing up, that we will not cheat death.

Stephen T. Asma: This is an interesting interpretation. The old metanarrative of resurrection is untenable in our skeptical and ironic age, but the deep drive for immortality can’t be squelched. Zombies also have unique qualities that trigger the dynamic of love/hate, attraction/repulsion. The zombie, like the vampire, is a kind of immortal: chop his leg off, he’s still coming; blow a hole in his chest, he’s still coming. His life span is indefinite and he’s indestructible. So the little narcissist inside us really likes the immortal aspect of the zombie and the vampire. We unconsciously crave that kind of staying power and durability, but our narcissistic desire to cheat death is impossible to sustain in the face of mature experience. Reality regularly reminds us, as we are growing up, that we will not cheat death.

We love to hate zombies because they simultaneously manifest our craving for immortality, and our more mature realization that the flesh always decays. As “living dead,” all zombies elicit those conflicting impulses in our psyche. The more disgusting they are, the more we are reminded of our inevitable decomposition, but the more they keep getting up and chasing, the more we are delighted by the promise of immortality. The psyche seems to carry out an unconscious vacillation: the zombies live on forever, those lucky sods, but wait…they’re disgusting and repellent and…and…run!

You’ve added another cultural dimension onto this psychological dynamic. We’re a post-Christian culture, but still in the grip of those old values and metaphysical aspirations. So, maybe zombies represent our now ironic and sardonic view of immortality.

TheoFantastique: Stephen, thank you again for the copy of your book, and for taking the time to discuss it here. It makes an important contribution to our historical and cultural understanding of monsters and the monstrous.

One Response to “Stephen T. Asma – On Monsters: An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears”