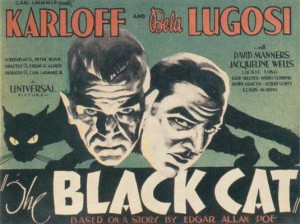

I have finished reading, and enjoying, The Philosophy of Horror, edited by Thomas Fahy (The University Press of Kentucky, 2010), and with this concluding post on the book I will comment on Paul Cantor’s chapter, “The Fall of the House of Ulmer: Europe vs. America in the Gothic Vision of The Black Cat“.

I have finished reading, and enjoying, The Philosophy of Horror, edited by Thomas Fahy (The University Press of Kentucky, 2010), and with this concluding post on the book I will comment on Paul Cantor’s chapter, “The Fall of the House of Ulmer: Europe vs. America in the Gothic Vision of The Black Cat“.

Cantor’s chapter was of great interest to me not only because it interacts with an often neglected Universal Studios horror film from the classic age, but also because Cantor brings a fascinating cultural and historical analysis to the subject matter. Cantor’s discussion focuses on the work of the director of The Black Cat, Edgar Ulmer. Ulmer was an immigrant to the U.S. from Europe who had experienced the darkness of World War I, and had also worked with German expressionist film directors. These experiences would come together to provide an interesting mix in The Black Cat.

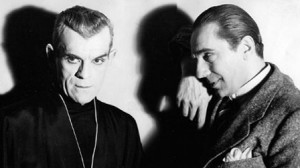

For those who have not seen the film, it tells the story of an American couple in Europe on their honeymoon who end up in the home of Hjalmar Poelzig (Boris Karloff) after being rescued from a bus accident by Vitus Werdegast (Bela Lugosi). As it turns out their stay with Poelzig is anything but an accident as they get caught up in a plot for revenge by Werdegast who seeks justice for his sufferings under Poelzig in the past during the Great War. We come to learn that Poelzig has an even darker side in that he has stolen Werdergast’s wife (who is now deceased), has been married to his own daughter, keeps the preserved corpses of his wives below his home, and is the high priest of a Satanic cult. As the film ends Werdegast finds his justice by torturing Poelzig and eventually blowing up his home, and with it the Satanic cult.

Although many fans familiar with this film no doubt enjoy it on the surface level of a Universal horror film involving two of classic horror’s greatest stars, Cantor reveals in his discussion that Ulmer worked in greater levels of depth into the film that drew upon his experiences. This includes not only various Gothic archetypes such as the dark and brooding home, the living dead, and incest, but also commentary that pits European sophistication against American naïveté, even while offering critique of European darkness and optimism about America’s possibilities. In Cantor’s view, “[t]he genius of The Black Cat lies in the way it maps the Gothic psychodynamics of the family onto a political landscape.” Ulmer accomplishes this as a European immigrant to America who had seen the horrors of the cultural situation which resulted in World War I, thus including an interesting and somewhat contradictory set of elements into the story. This involves the depiction of the “innocent” American travelers from a “low culture” background who are contrasted with the more sophisticated, yet potentially dangerous Europeans from a “high culture” background. As Cantor describes the depictions of these characters, the Europeans

Although many fans familiar with this film no doubt enjoy it on the surface level of a Universal horror film involving two of classic horror’s greatest stars, Cantor reveals in his discussion that Ulmer worked in greater levels of depth into the film that drew upon his experiences. This includes not only various Gothic archetypes such as the dark and brooding home, the living dead, and incest, but also commentary that pits European sophistication against American naïveté, even while offering critique of European darkness and optimism about America’s possibilities. In Cantor’s view, “[t]he genius of The Black Cat lies in the way it maps the Gothic psychodynamics of the family onto a political landscape.” Ulmer accomplishes this as a European immigrant to America who had seen the horrors of the cultural situation which resulted in World War I, thus including an interesting and somewhat contradictory set of elements into the story. This involves the depiction of the “innocent” American travelers from a “low culture” background who are contrasted with the more sophisticated, yet potentially dangerous Europeans from a “high culture” background. As Cantor describes the depictions of these characters, the Europeans

are deeply neurotic, obsessive-compulsive, and self-destructive, not to mention downright evil and even Satanic, while the Americans are free, open, good-natured, and optimistic. But at the same time the Europeans are simply more interesting than the Americans. The Europeans are intelligent, cultured, and artistic, while the Americans are bland, prosaic, and more than a little obtuse.

It is Cantor’s view that Ulmer, through the vehicle of a horror film, was trying to work through the medium of pop culture in order to “tell a deeply serious tale of European tragedy.” Indeed, Ulmer’s lingering concerns over Europe not only looked back with concerns over the “horrors of World War I and, as a result, bordering on the bring of madness, ready to plunge into a nihilistic abyss,” but also sounded a warning of cultural dynamics that made possible the great evils of World War II.

It is Cantor’s view that Ulmer, through the vehicle of a horror film, was trying to work through the medium of pop culture in order to “tell a deeply serious tale of European tragedy.” Indeed, Ulmer’s lingering concerns over Europe not only looked back with concerns over the “horrors of World War I and, as a result, bordering on the bring of madness, ready to plunge into a nihilistic abyss,” but also sounded a warning of cultural dynamics that made possible the great evils of World War II.

Fans of classic Universal horror, as well as students of culture and history, will find a great deal to reflect upon in Ulmer’s masterpiece of The Black Cat. As Cantor concludes:

Along with the other European émigrés who directed horror movies in the 1930s, [Ulmer] helped make the avant-garde cinematic techniques of the German expressionists part of the Hollywood mainstream. In the end Ulmer’s project in The Black Cat is internally contradictory — to create a very European movie to argue for the cultural independence of America. Fortunately for him and us, this self-defeating quest resulted in a horror movie masterpiece, an unusually thoughtful product of pop culture that philosophically reflects on the relationship of pop culture to high culture.

The Black Cat can be added to the reader’s DVD library as part of The Bela Lugosi Collection.

There are no responses yet